Blog Archives

A Look at Neo-Noir in Michael Jackson’s Short Films

Willa: Last April Nina Fonoroff joined me for an interesting discussion about Billie Jean and Michael Jackson’s use of film noir. After that post went up, Elizabeth Amisu posted a couple of comments here and here about “neo-noir” in both Billie Jean and especially Who Is It. I was very intrigued by this since I’d never even heard of neo-noir, so I began talking with Elizabeth about it, and she very generously provided me with some introductory reading to help bring me up to speed – though I’m still very much a neophyte.

So today, Lisha and I are excited to be joined by both Elizabeth and Karin Merx to talk about neo-noir and how it can provide new ways of seeing and thinking about Who Is It, Billie Jean, Smooth Criminal, and other short films. Elizabeth is a lecturer of English Literature and Film Studies, and her ongoing academic research focuses on “high-status representations of black people” in the plays of Shakespeare and his contemporaries. Her book, The Dangerous Philosophies of Michael Jackson: His Music, His Persona, and His Artistic Afterlife, is being published by Praeger in August. Karin is both an academic and a classically trained musician, and she is currently completing her doctoral research in Art History. Last year she published an essay on Michael Jackson’s Stranger in Moscow. Together, Elizabeth and Karin co-founded and co-edit the Journal of Michael Jackson Academic Studies, which is a wonderful resource for anyone wanting to learn more about Michael Jackson’s art.

Thank you so much for joining us, Elizabeth and Karin! I’m really eager to learn more about neo-noir and how you see it functioning in Michael Jackson’s short films.

Elizabeth: Thank you very much for having us here on Dancing with the Elephant, Willa. It’s a real pleasure to have this conversation with you.

Karin: Thank you, Willa, for having us.

Willa: Oh, I really appreciate the chance to talk with both of you and learn more about this! So what exactly is neo-noir? I know from my conversations with Nina that noir can be really difficult to define. So how do you identify neo-noir when you see it, and how is it different from noir?

Elizabeth: That’s a very good place to start, Willa, because noir forces us to really question the way we define genre in the first place. It includes titles like The Maltese Falcon and The Big Sleep, and a whole series of Hollywood films released between 1941 and 1958, whose dark subject matter and cinematic style reflected the negative mood during and after World War II. Noir has easily recognisable and distinctive visual and thematic features, such as a striking use of silhouettes, low-key lighting, femme fatales, confessional voiceovers and dangerous urban landscapes.

Neo-noir, however, emerged in the 70s, 80s and 90s, and it comes in lots of forms, from modern-day attempts at pure noir films, to science-fiction and thrillers. A few key titles are The Usual Suspects, Blade Runner, L.A. Confidential, Se7en, Sin City, and one of my particular favourites, Drive. However, one of the most humorous places to see a noir-style pastiche is the American Dad episode, Star Trek.

Willa: Wow, Elizabeth, that list covers a really broad range. It sounds like neo-noir can be even more difficult to pin down than noir itself …

Elizabeth: Yep, you are so right. It’s that slipperiness of the term which causes so much debate. However, I think that’s what makes noir so fun for discussion. There is never a simple or straightforward answer. One cool thing about noir-style is that it translates across other genres, so Blade Runner is science-fiction, Se7en is a crime thriller, and The Usual Suspects is more of a mystery.

Lisha: Whoa. Hold up for a second here, because I’ll admit that when it comes to film noir, I still think of the instantly recognizable black-and-white Hollywood movie formula with all the cigarette smoking and a private detective in a snap-brim hat tracking down a bunch of shady characters. So can you tell us just a little more about the issues that make noir so difficult to pin down as a genre or style?

Elizabeth: You have a point, Lisha. For a lot of people noir is superficial, but for others noir’s heart lies in its themes rather than the visuals. The word does, however, mean “black film” and it actually grew out of the German Expressionism movement. The films were initially dark because of low-budget requirements.

In Double Indemnity, directed by Billy Wilder (Willa and Nina’s discussion on Billie Jean featured it) the real darkness was found in the idea that the nicest guy in the world, Walter Neff (played by Fred MacMurray), found himself moving down a path of destruction. There’s a line he says, “I couldn’t hear my own footsteps. It was the walk of a dead man.” He loses himself entirely because he thinks he can commit murder and get away with it.

That loss of self is very noir. So it’s the head-game, the psychological downfall, which always makes a noir film so compelling.

Lisha: Why do you think noir has been so irresistible for generations of filmmakers to copy as neo-noir? What accounts for its long-lasting appeal?

Elizabeth: That’s hard to say. It’s definitely true that the noir movement ended before the sixties. It just didn’t chime with the popularity of free love and liberation. However, when there’s a significant downturn, political intrigue, war and espionage, noir-style and noir-themes show up time and again.

Karin: Styles or tendencies are often revisited by artists, hence the word “neo,” from “neos” meaning “young” in the Greek. So we have words like “neo-expressionism.”

Elizabeth: Of course everyone knows the character Neo from the film, The Matrix. He is the “one,” the young saviour.

Willa: That’s interesting. So it sounds like filmmakers – and audiences too – are drawn to noir and neo-noir when they’re feeling anxious, like during a war or recession or other social unrest.

Lisha: It’s as if social events dictate when artistic themes become relevant again.

Karin: Yes, Willa and Lisha, artists are sensitive to what happens in society, and often use the general dissatisfaction with what is going on in their art. Sometimes even ahead of time.

Willa: Like when the panther dance in Black or White seemed to anticipate the Rodney King riots, as Joe Vogel pointed out in his article, “I Ain’t Scared of No Sheets: Re-screening Black Masculinity in Michael Jackson’s Black or White.”

Lisha: Great example, Willa.

Elizabeth: Also, a noir-style film can be quite compelling on a relatively low budget, which also makes them quite appealing for filmmakers. We are now a far more complex and savvy film-going audience, so a traditional noir film may not appeal to viewers as much as a sexy nostalgic homage (a respectful and admiring nod) to the past, as in L.A. Confidential.

Lisha: That’s true. Movie-goers have come to expect extremely high production values. Although I suspect some of the old films noirs still enjoy some popularity by intersecting with our notion of the “classic.”

Eliza, you also mentioned the term “noir-style pastiche,” so I’m wondering how we might define the term “pastiche.”

Elizabeth: A pastiche is how we term a work of art that is mostly an imitation of another. One film that always ends up in pastiche is the epic film, Spartacus, with people saying, “I am Spartacus!” A pastiche is usually a celebration rather than a mocking of source material. Imitation for comic effect is parody.

Lisha: That’s a good point to keep in mind, that imitation can take many forms – from a nostalgic homage to a parody or spoof. So would you say neo-noir is roughly equivalent to noir-style pastiche? Or does pastiche require a recognizable intertextual reference to a specific work?

Elizabeth: Yes, it would be very apt to refer to neo-noir as film noir in pastiche. Several neo-noir films reference quite specific works but that is not necessary to term a work a pastiche.

Karin: I agree, Elizabeth. Also pastiche is more something we use in postmodernism, by way of using elements we all recognise but put in another context.

Lisha: A tricky example might be Michael Jackson’s engagement with film noir in This Is It. In his Smooth Criminal vignette, he doesn’t imitate the genre as much as he literally inserts himself into noir classics like Gilda and The Big Sleep. Here’s a link:

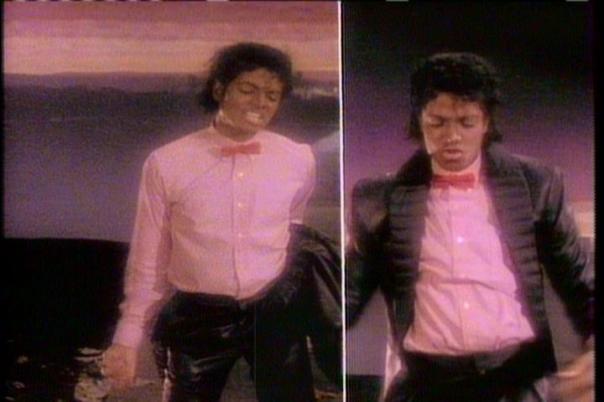

Elizabeth: It’s so interesting that you say this, Lisha, because I was writing about this in my final edit of my book this morning. I dedicate an entire chapter to Jackson’s use of fashion, and in it I write about how he really made himself part of HIStory by integrating his image into that of classic Hollywood cinema. There’s something so warm and sumptuous about 1930s to 1950s cinema and it’s so clear from Smooth Criminal that this was his intention, to place himself within a classic era in the minds of his viewers.

Willa: Yes, I agree, though it’s also interesting to think about what might have attracted him in terms of the themes of Gilda and The Big Sleep, where nothing is as it seems and we’re never sure who we can trust.

Eliza: I didn’t even think of that. You are so right, Willa. That theme of “trust” is one of the most overarching themes in Jackson’s work, don’t you think? I thought of the moment in Smooth Criminal when the man with the pinstripe suit tries to stab him in the back.

Willa: Wow, what an incredible image! And this screen shot does look very noir, especially when frozen in time like this.

Lisha: It really does. Even though the film is in color, it still manages to capture the shadowy chiaroscuro lighting associated with black and white noir.

And that’s a perfect example, Eliza, on the theme of “trust.” It’s as if Michael Jackson’s character has grown eyes in the back of his head from having to constantly watch his back. Now that you mention it, I do think “trust” is an important overarching theme in Michael Jackson’s work. I’m surprised I hadn’t thought about it before.

Willa, didn’t you identify “Annie, are you ok?” as sort of anti-noir, in that it is a gesture of care and concern for the female character, Annie, rather than an assumption that she is a dangerous femme fatale who needs to be killed off by the heroic male protagonist? In this example, Michael Jackson engages with the film noir theme of distrust, while sharply departing from it at the same time.

Willa: Yes, so this is another kind of imitation – neither homage nor parody, but evoking a classic work from the past in order to rewrite it.

Lisha: That is such a fascinating and inspiring idea. I noticed another gendered anti-noir move in Smooth Criminal, in the instrumental break, when we see a beautiful female jazz saxophone player on the bandstand.

Musically speaking, jazz saxophone is the apotheosis of all noir cliches, and it strongly codes male. In film noir, the saxophone is typically heard when a sexy female appears on screen, as a sort of male cat call. In Smooth Criminal we never actually hear a saxophone – there’s no saxophone in the song – but we see a sax player onstage as a visual imitation of noir. However, it isn’t one of the boys in the band as we might expect. It’s a beautiful female musician looking somewhat glamorous in her fancy dress.

This strikes me as going against the way jazz saxophone is generically used in film noir. The image of a female saxophone player both engages our memory of film noir and disrupts it at the same time.

Willa: That’s really interesting, Lisha. It’s kind of similar to how he used Jennifer Batten and Orianthi in concert to both evoke and disrupt our ideas about hard rock guitarists.

Lisha: That’s exactly what I was thinking!

Of course many fans understand Smooth Criminal as a specific intertextual reference to “Girl Hunt Ballet,” the play-within-a-movie from Vincente Minnelli’s The Band Wagon. I think most Michael Jackson insiders would rightly point to Smooth Criminal as a heart-felt homage to Fred Astaire.

Willa: Yes, and one of the first things Fred Astaire’s character says in “Girl Hunt” is “Somewhere in a furnished room a guy was practicing on a horn. It was a lonesome sound. It crawled on my spine.” Which could evoke an image of a saxophone …

Lisha: You’re so right, Willa! That scene highlights what an important element jazz is in classic film noir. Although I do believe it is a trumpet player in that scene, not a sax player, if I remember correctly.

Willa: Oh, you’re right. I should know better than to trust my memory! I just watched that opening scene again, and we do hear a trumpet playing in the background, and even catch a glimpse of it through an open window. Here’s a clip of “Girl Hunt Ballet,” and the trumpet appears about a minute in:

Lisha: The Band Wagon is pretty interesting in and of itself, because I think we could interpret “Girl Hunt Ballet” as a noir-style pastiche, even though it was made in 1953, during the same time period classic films noirs were still being made.

So I wonder if pastiche plays an important role in genre formation itself, since pastiche identifies the specific elements that are needed for a successful imitation?

Willa: Wow, that’s a really interesting idea, Lisha! It reminds me of Lorena Turner’s work with Michael Jackson impersonators, and how they lead us to a better understanding of Michael Jackson’s iconography. What exactly is needed to “be” Michael Jackson? Through the impersonators Lorena photographed, it becomes clear that you really don’t need to physically look like Michael Jackson, his face and body – you simply need a glove, a fedora, and a distinctive pose, for example, or maybe a red leather jacket with a strong V cut.

So those “imitators” help us identify what is essential about Michael Jackson’s star text, just as you suggest that pastiche (like neo-noir) helps us identify what is essential to a given genre (like noir).

Lisha: Exactly! Perhaps we should think of Smooth Criminal as a noir pastiche of a noir pastiche?

Willa: Wow. So you’re saying that neo-noir is a pastiche of noir, and Smooth Criminal is a pastiche of neo-noir, so it’s a noir pastiche of a noir pastiche? Do I have that right?

Lisha: Too funny! Yes, I think I just suggested something crazy like that.

Willa: Ok, I’m really going to have to think about that … but it does sound like the kind of loop-de-loop reference that Michael Jackson loved …

So a director who is frequently mentioned in discussions of neo-noir is David Fincher, who directed Michael Jackson’s Who Is It video in 1993. For complicated reasons that aren’t very clear, there were actually two videos made for Who Is It. Joie talked about this a little bit in a post we did a couple years ago. The second version is simply a montage of concert and video clips, but for some reason it seems to be the “official” one – for example, it’s the one that was released in the US when the song debuted, and it’s the version available on the Michael Jackson channel of Vevo.

So the David Fincher version has not been widely viewed and can be a little difficult to find online, but here’s an HD version of it on YouTube:

Elizabeth: It’s relevant that the Who Is It short film included in the Dangerous Short Films anthology was the one Fincher directed.

Willa: That’s true, and it’s in the Vision boxed set also, so it has some degree of official acceptance. That’s a good point, Elizabeth.

So I love this short film, and it does have a very noir-ish feel to it, doesn’t it? What are some specific visual elements you see in Who Is It that help create that noir-type mood or feeling?

Elizabeth: It uses many of the specific visual elements Fincher used in his feature films in the following years – Se7en (1995), Fight Club (1999) and much later, The Social Network (2010) – such as the repeated use of low-key lighting throughout the sequences to create an ominous tone and a sense of foreboding. Fincher also uses stark white light, as in the scene towards the end with the female character weeping, or he uses very muted lighting, where fluorescent bulbs don’t really illuminate the corners of the space.

Willa: Yes, and that’s pretty unusual, isn’t it? For example, here’s a screen capture from about 5:20 minutes, when the female lead is at the gate and the manager character won’t let her in. You can see that the edges of the shot are dark and uneven, as if the picture field weren’t fully exposed.

There are also scenes where the light is coming from below, which is pretty unsettling. We’re used to light coming from above, like sunlight, and we rarely see faces, especially, lit from below, unless it’s a 50s-style horror movie. Here’s a screen capture from about 4:20 minutes in with the light shining up from under the character’s faces:

It really makes them look eerie and artificial, like store mannequins.

Elizabeth: The store mannequins, oh yes. Nice observation, Willa. And that whole idea links to this sense of being plastic and fake, not quite real. We can’t quite trust what they say because, although they seem human, they aren’t. And this extends to the words they say and the theme of the song. In terms of the lighting, I really enjoy the fact that the light seems drowned out by the encroaching darkness.

And of course, there are so many shots where only half of a face is illuminated, giving us a sense that the characters are being duplicitous and untrustworthy. Isn’t that what Who is It is all about? Who can we trust? Who has betrayed us?

Willa: Exactly. And you’re right, there are numerous shots where a face is only partially lit, suggesting we don’t see that person completely – not their face, their motives, or their character. So even something as subtle as lighting reinforces the meaning of the film and the lyrics. Who can we trust?, as you say. And it isn’t just the shape-shifting female lead, the one who goes by so many different names (Alex, Diana, Celeste, Eve, … ). All of the characters are pretty shadowy – both psychologically and visually. It’s not clear that we can trust anyone.

Elizabeth: You’re right, Willa. And what you’ve highlighted is how amazing Michael Jackson was when it comes to linking across his mediums – song complements short film complements costume and so on and so forth. What is also quite clear is that there is an exchange of money going on for sexual services, which makes the nameless female lead into a literal “object” of desire.

Lisha: You know, the money for sex is something I find confusing in this film. When I see the world of rarefied luxury and helicopter travel depicted here, I’m thinking extremely high stakes. The wardrobe and makeup artists employed to execute these spectacular acts of duplicity evoke the world of espionage, corporate or national security, and figures in the hundreds of millions or billions. The level of intrigue seems to go way beyond the mere sexual encounter, although that is clearly one aspect of the betrayal and psychological torture going on. What do you think?

Elizabeth: Oooh Lisha, that is a cool point. You are very right that what seems to be at stake is far more than sex.

Willa: I agree. It does seem to be more like very high stakes espionage.

Elizabeth: The Second World War was famed for its duplicitous female agents, using their womanly wiles to tempt secrets out of the (predominantly male) opposition. However, I also find it quite interesting that the character of the high-end sex-worker has a value far higher than the average viewer might expect. This is a character who obviously serves very wealthy clients and tends to their every whim.

Either way, it’s a particularly dark theme. I like to think of Michael as the femme fatale himself. Two authors have discussed this in some depth: Susan Fast in Bloomsbury’s Dangerous, and Marjorie Garber in Vested Interests. Both wrote on Jackson’s crossing of the male-female binary. In one interview Karen Faye, Jackson’s personal makeup artist, stated he didn’t accept these binaries at all. He built his aesthetics (identification of beauty) on a level that went beyond masculine/feminine.

Karin: I agree, Elizabeth. I think he built his aesthetics way beyond the binary of male/female. He always thought of human beings as being all the same.

Elizabeth: And we all have feminine and masculine qualities. It really is two halves of a whole. Notions of femininity and masculinity are really constructed by society and ideologies which have no basis in biology or reality. They are obstacles we put in our own way and MJ wasn’t interested in them. But bringing it back to the theme of neo-noir is the idea of binaries too, because the femme fatale is dangerous because of her unrestrained sexuality and her ambiguous morals.

Karin: This ambiguity is what we see so well in Who Is It.

Elizabeth: You are so correct, Karin. This is another link to Billie Jean and is found in the shots below, again the bed becomes a place of intrigue. There are physical and nonphysical exchanges here that we (as an audience) are not privy to. So we must decide for ourselves what is going on, and this heightens the mystery.

Willa: That’s a really good point, Elizabeth, and this scene is evocative of the bed scene in Billie Jean, isn’t it?

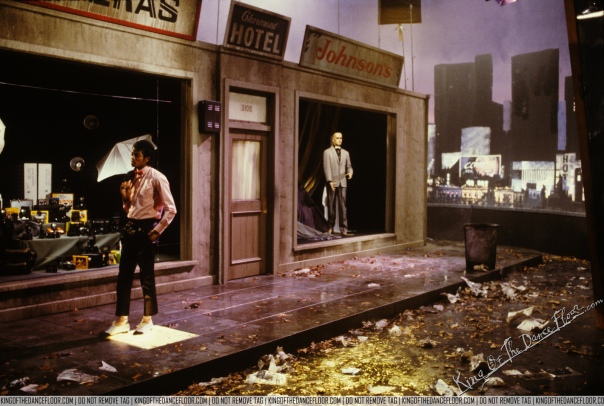

Elizabeth: Yes it is, Willa. It also shows us how MJ references his own work. Other specific visual elements that Fincher often uses are found within the city itself, and I love how, in his work, the city is often given its own personality.

In Who Is It the city is presented as a golden otherworldly labyrinth that Jackson is separated/protected from by a glass wall. He is distanced from the society in which he lives, much like all of Fincher’s subsequent neo-noir protagonists. There are angel statues on the cover of the Dangerous album and they appear again in the city, bringing to mind the City of Angels, Los Angeles, which is ironic, of course, because “all that glitters (see the shot below) is not gold.”

Lisha: That is such a beautiful screen shot, Eliza. I’m wondering why I’ve never zeroed in on that before. He is in a major urban area, enjoying all the economic advantages the city has to offer, yet he is so completely isolated and alienated at the same time. The paradox is communicated by a sheet of glass.

Willa: Yes, and we see that same motif repeated in Stranger in Moscow. That film opens with a shot of a man seen through the glass of his apartment window, eating his supper from a can. Then we cut to a scene of a sad-looking woman in a coffee shop, but again we’re looking at her through a glass wall. And then there’s that wonderful scene about 3:05 minutes in where the man in his apartment sees the kids outside running through the rain, and then reaches up and touches the glass. Here’s a screen capture:

Lisha: That is such a strong image.

Willa: I agree. I love that moment, and think the glass imagery here functions like the glass wall in Who Is It. As you said, Elizabeth, this character “is within society but separated from it.” But I think this character begins to regret his isolation after seeing the kids run through the puddles, and that’s when he makes the decision to go outside and stand in the rain, and begin to experience life more fully.

Elizabeth: Oh yes, and only if he leaves his glass prison, can he hope to begin to communicate with those around him.

Karin: The difference with Stranger in Moscow is that it is not Michael behind a window that separates him from society, but the black man and the sad woman who play a role in the short film. Michael is walking the dark gritty streets of “Moscow” and, as I analyzed in my essay “From Throne to Wilderness: Michael Jackson’s ‘Stranger in Moscow’ and the Foucauldian Outlaw,” I believe he is separated but also separates himself from society in a different way. To me, he is also not part of the five people who are clearly abandoned from the so-called “normal” world. Michael seems to be separated by his “glowing face,” a face we can also see in the black and white sequence in the short film Bad.

Stranger in Moscow has this very estranged, alienated mood. The loneliness is dripping from the screen and is emphasised by the slow motion, which is not typical for noir but definitely for neo-noir. I think it is mainly the mood in Stranger in Moscow that is very neo-noir.

Lisha: I didn’t realize slow motion was characteristic of neo-noir, Karin. I’m fascinated by how the sense of alienation in Stranger is depicted through two distinct temporalities happening at once. Michael Jackson was filmed in front of a blue screen singing and walking very slowly on a treadmill, which was later added to the slow motion background. So as he sings in real time with the music, everyone and everything else is moving in slow motion, like some kind of separate, alternate reality.

Willa: Yes, that’s a very important observation, Lisha. It’s so interesting how slow motion is used in Stranger in Moscow. When we look at the city directly, everyone and everything moves at normal speed. But when it’s implied that we’re looking at the city from the perspective of one of the isolated people – the woman sitting alone in the coffee shop, or the homeless man lying by the sidewalk, or the teenager watching other kids play ball, or the man eating supper from a can, or the businessman watching pigeons, or even Michael Jackson himself – the world suddenly appears to be moving very slowly. Even the raindrops fall in slow motion.

Lisha: Wow, Willa, that’s exactly it. The slow motion is the perspective of those who are not participating in the normal rhythms of the city.

Willa: Exactly. Or who do participate to some degree, like the man with the pigeons or the woman in the coffee shop – both of them are wearing business suits – but who still feel disconnected from those rhythms. At least, that’s how it seems to me.

For example, we see pedestrians walking by the coffee shop, and they’re walking at normal speed. But then the scene shifts and we see the lonely woman watching the pedestrians, and now they seem to be moving in slow motion. So when we’re looking at them through her eyes, as it were, they’re moving in this oddly decelerated way. But she herself isn’t – she’s still moving at normal speed.

That difference in film speed creates a dislocation between those isolated people and the pedestrians who pass them by, and that disconnect is very effective at emphasizing just how detached they are from the world around them. As you write in your article, Karin,

On the one hand, the slow motion has the function of magnifying emotion, and on the other hand it shows two distinct worlds and the distance between those two worlds.

I agree completely. It also seems to be trying to capture or re-create the sensory experience of depression – of what it feels like to be in a bustling world when you are depressed and out of sync with everyone around you.

Lisha: It’s such a powerful visual depiction of “How does it feel, when you’re alone and it’s cold outside?”

Willa: I agree.

Lisha: And it allows us to inhabit the perspective of those five characters you mentioned, Karin, who are “clearly abandoned from the so-called ‘normal’ world.”

Getting back to what you said earlier, I’ve always been fascinated by the choices Michael Jackson made in this film to achieve such a glowing, colorless look for his face.

Karin: Yes, Lisha, it is as if he wants to disappear into the mass, the streets and the people walking around him.

Elizabeth: I agree wholeheartedly. It’s particularly interesting when we look at Michael’s use of his face and the concept of “masquing” and “masque” culture. This is an extended metaphor about identity in many neo-noir films, and one that Michael uses to articulate his relationship with his audience. They always seem to be wondering “who is he?”

Willa: Which refers us back again to Who Is It. Masques are a recurring theme in that film as well – from the oddly blank face we see rising beneath the white blotter on the desk or pushing out from behind the white wall, to the disguises worn by the Alex/Diana/Celeste/Eve character as she shifts identities, to the more subtle subterfuges of other characters as they decide what to reveal and what to keep hidden. We don’t truly know anyone in that film, not even Michael Jackson’s character, though the song accompanying the film is written from his point of view. So while we may be inside his mind to some extent, he is still somewhat distant and unknowable.

Elizabeth: Notions about identity are at the forefront of neo-noir films, especially in terms of being an individual in a society. No one is exempt from feeling alienated from others, and without our connection to others, how do we know that we are alive?

Karin: In the article “Eighties Noir: The Dissenting Voice in Reagan’s America” in The Journal of Popular Film and Television, Robert Arnett writes about the “face mask motif” that “furthers the analogy between the undercover plot device and ’80s visual media obsession.” In your article “Bad (1987),” Elizabeth, you write about the extreme close up in the black and white part and refer to it as act of defiance.

It is interesting to see how Michael used his own face, which was seen by the public as a mask, as “an act of defiance” in Bad because there was so much speculation in the tabloid media about his face. The mask as described by Arnett is “revered and experienced as a veritable apparition of the mythical being it represents.” However, in Bad, he does not represent himself as a mythical being but as himself in a “look at me, this is who I am” kind of way.

In Stranger in Moscow his “mask” is referring to him as a simple human being who walks the streets of Moscow. However, his glowing face-mask distinguishes him from all the other faces around him, which gives it this mythical representation, as if he has no connection to others anymore.

Willa: Yes, and that sense of alienation from society seems very noirish. As Nina said,

So many noir films convey a story about the way characters struggle with both internal and external forces to maintain their moral integrity in a fundamentally corrupt world.

That’s a good description of both Who Is It and Stranger in Moscow – and Bad also, as you mentioned, Karin. There’s a similar theme in Smooth Criminal, You Rock My World, Give In to Me, and others as well. In all of these films, the world is “fundamentally corrupt,” and Michael Jackson’s character must figure out how to negotiate that corruption without becoming tainted himself.

You know, I hadn’t really thought about it before, but that’s a recurring theme in Michael Jackson’s work, isn’t it? For example, if I think about his early videos, meaning the three videos from the Thriller album, that’s precisely what Beat It and Billie Jean are about – an innocent young man negotiating a corrupt world. But then Thriller complicates that. We’re never sure about the main character, Michael – about whether he’s innocent or not. He’s constantly shifting back and forth between a sweet, guileless teenage boy and a monster/zombie, between an innocent and the very epitome of corruption.

Elizabeth: Now we’re really taking it to another level: Jackson’s use of complex innocence and corruption themes is an entire theme in itself. The ambiguity, or what one could call the liminality of innocence, is what Jackson negotiates, don’t you think? The notions we have of the innocent and who is innocent. It comes up again and again. He never gives us a truly straight answer. In Smooth Criminal he is good but he commits violence throughout the sequences, in Thriller he’s the heartthrob and the zombie, and in Bad he is the innocent schoolboy and “bad” as he starts a dance-fight in a subway.

Lisha: And doesn’t that lead us right back to the issue of perspective? I feel like this is especially clear in Thriller, if we think about how we can experience the character “Michael” through his girlfriend’s eyes. As she is overwhelmed by the excitement of being in love, she sees and experiences a “thrill-her” date with her handsome new boyfriend. When she begins to fear where all this might take her, she sees and experiences a scary creature from a “thriller” horror film.

The girlfriend’s experience is dependent upon what she brings to the table at any particular moment in time. When she looks at the world through the perspective of love, she sees beauty. When she looks at the world through fear, she sees a monster.

Willa: Wow, that is so interesting, Lisha! As many times as I’ve watched Thriller, I’ve never thought about it that way before.

Lisha: Isn’t that a perfect reflection of how we collectively experience Michael Jackson? He is an angel or a devil, innocent or guilty, depending on what the viewer brings to the table. This ambiguity forces us to question the whole concept of reality, showing us how perception trumps what is “really there.”

Willa: Yes, that’s a really important connection. And I agree, Elizabeth, that he does seem to be exploring the grey areas between guilt and innocence – “the liminality of innocence,” as you called it – and I love those examples you gave. He may be positioned in the hero role in Smooth Criminal, but he commits numerous acts of violence, as you say. And in Billie Jean, he may not be the father of the child whose “eyes looked like mine,” but he did go to her room and something – we’re not sure what – “happened much too soon.” That ambiguity occurs throughout Michael Jackson’s work.

Elizabeth: However, one short film which is definitely not ambiguous is Scream, and it’s one we should definitely mention before closing because it has a lot of noir-esque features (including a heightened mood of alienation). It is set in the vacuum of space and “in space, no one can hear you scream.” Putting Michael and Janet in this off-world environment really heightens the connection between alienation and celebrity/fame.

Karin: Yes, they surrounded themselves with art, which is often qualified as higher status and more distanced from people. So the art with which they surround themselves in their spacecraft world can also be seen as an alienating aspect.

Elizabeth: Not only do they surround themselves with art, they also attempt things on their own or in a pair that would usually be done in a group, such as playing sports, playing music. What we see in Scream is more escapism, a self-imposed exile. These are two characters in exile, and they have been put as far from their fellow human beings as possible. They can only connect through screens and other conduits. We get a sense that they are trying desperately to amuse themselves and all of it is in vain. The up-tempo beat of the song contradicts sharply with this.

Lisha: Wow, Elizabeth! Never in a million years would I thought of Scream in terms of neo-noir, but there it is! Mind blown.

Willa: I agree. I wouldn’t have thought of Scream as neo-noir either, but it makes so much sense now that you say that, Elizabeth. All the elements we’ve been talking about, from visual elements like high-contrast lighting to thematic elements like isolation and the difficulty of being an innocent individual confronted by a corrupt society – they’re all there, aren’t they?

Elizabeth: Yes they are, Willa, Lisha. It’s one of those things that strikes you in a really uncanny way – that Scream which is free from all the stereotypes of noir is in fact very clearly neo-noir and dealing with so many of those ideas. Don’t you think that the space location serves to heighten the noir-ness of Scream?

Lisha: Most definitely. And with the sad news of David Bowie’s passing, I can’t help relating Scream to Bowie’s 1969 Space Oddity.

Bowie’s character “Major Tom,” was inspired by Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey. Bowie said he strongly identified with its sense of isolation and alienation. I definitely see a lot of this work in Scream.

Willa: You know, we should talk about that sometime. There are a lot of connections there to Michael Jackson, as you say. Elizabeth, Karin – would you like to join us in that discussion?

Elizabeth: I would love to join you guys for a Bowie post. Can’t wait.

Karin: Yes, of course. I love Bowie and have listened to his music, and read a lot about him. So I’d be excited for that.

Willa: Wonderful! And thank you both so much for educating us about neo-noir! It really opened my eyes and allowed me to see some of his films in ways I never had before. I really value that, so thank you sincerely.

I’d also like to let everyone know that our friend Toni Bowers has an article about Michael Jackson and biography coming out soon in the Los Angeles Review of Books – next Tuesday, I believe. I’ll post a link as soon as it goes up, but you may want to keep a lookout for it.

More Like a Movie Scene, part 3

There was nothing left of the guy, nothing at all – except a bone, a rag, a hank of hair. The guy had been trying to tell me something … but what?

– The Band Wagon (1953)

Willa: A few months ago I was joined by Nina Fonoroff, who is both a professor of cinematic arts and an independent filmmaker. We did a post about the first section of Billie Jean, and also talked about how Michael Jackson drew inspiration from the Fred Astaire movie The Band Wagon, and from film noir more generally. Then a few weeks later Nina joined me for a second post about the middle section of Billie Jean, and Nina suggested fascinating visual connections to The Wizard of Oz and The Wiz. Today we are continuing this discussion by looking at the concluding scenes of Billie Jean and some potential visual allusions in that section of the film.

Thank you so much for joining me, Nina!

Nina: Thank you, Willa! I’m hoping we’ll find a new wrinkle in the “case” of Billie Jean (the film).

Willa: Oh, I always discover something new whenever I talk with you!

So last time we looked at Michael Jackson’s iconic dance sequence in the middle of Billie Jean, with the bleak ribbon of road stretching behind him to the foreboding “Mauve City” in the background. As you described so well, it’s like the antithesis of the shining “Emerald City” we see glistening at the end Yellow Brick Road in The Wizard of Oz and The Wiz, which of course featured Michael Jackson as the Scarecrow. I’m still very intrigued by that, and by your discussion of how those visual landscapes function within each film.

So that’s where we left off last time. The “Mauve City” dance sequence begins at about the 1:50 minute mark and extends to about 3:25, but about 2:45 minutes in we begin to transition into the final section of the film. First we cut to a view of Billie Jean’s bedroom – the first time we’ve seen it – and that’s followed by a series of snapshot-type images of her room. They’re kind of awkwardly framed, and almost look like  something a paparazzo or intruder might take.

something a paparazzo or intruder might take.

And then we immediately jump to the detective out on the street picking up a tiger-print rag. It’s the same rag Michael Jackson’s character pulled from his pocket in the opening scenes and used to wipe his shoe. And as we’ve talked about before, this is another connection to The Band Wagon, right?

Nina: Yes, it looks like a direct homage to the musical The Band Wagon, and specifically to a song-and-dance number within it, the “Girl Hunt Ballet,” which we’ve mentioned before. In this play-within-the-movie, Fred Astaire, who plays a character named Tony Hunter in the larger movie, and who stars in this sequence, begins his narration:

Nina: Yes, it looks like a direct homage to the musical The Band Wagon, and specifically to a song-and-dance number within it, the “Girl Hunt Ballet,” which we’ve mentioned before. In this play-within-the-movie, Fred Astaire, who plays a character named Tony Hunter in the larger movie, and who stars in this sequence, begins his narration:

The city was asleep. The joints were closed, the rats, the hoods, and the killers were in their holes. I hate killers. My name is Rod Riley. I’m a detective. Somewhere, some guy in a furnished room was practicing his horn. It was a lonesome sound. It crawled on my spine. I’d just finished a tough case, I was ready to hit the sack….

All of the well-worn tropes of the noir genre are present here: in the images, the sounds, the music, the feelings Astaire’s character mentions (lonesomeness, having personal vendettas – “I hate killers”) and his attitude of guarded nonchalance as he lights his cigarette. Later in the scene, another man appears in a trenchcoat and hat. We see him from a low angle as he emerges out of a thick fog and walks toward Riley. After picking a bottle up from the street and examining it, the strange man disappears, literally, in a flame and a cloud of smoke. And this is where Riley says,

There was nothing left of the guy! Nothing at all – except a bone, a rag, a hank of hair. The guy had been trying to tell me something. But what?

The detective is left with an enigma which compels him to pursue the disappearing man, while also falling prey to the femme fatale (played by Cyd Charisse), who doubles as a hapless victim whom Riley wants to protect until she betrays him. The whole “Girl Hunt Ballet” is an affectionate parody of the film noir genre at its apogee in the 1950s.

And in Billie Jean, too, we find many of the same elements: enigmatic characters, mysteries, clues, pursuits, deceptions, and reversals. These are deeply, if subtly, present in the story, the lyrics, the sounds, and the varied images of the short film as a whole – and many of our own responses, as we watch and listen to it.

First, there are a few different pursuits going on in Billie Jean. There’s the detective’s pursuit of his elusive prey, a disappearing man, Michael – though Michael is clearly no “killer.”

Then, Michael is the narrator of the story as well as the star of the show. Through his demeanor, his lyrics, and the whole story and setting of Billie Jean (song and film), Michael is an enigma to himself. He must consider why he has done the things he has done, that have caused him such remorse. One of his aims may be to attain self-knowledge – which I believe is what the song is ultimately about.

Finally, there’s our own perplexity, as we sort out the scattered clues that Michael Jackson himself – as our object of pursuit, our enigma, and our hero – has left behind. Aren’t we continually “going after” this man in our search for what he was “trying to tell us”? As fans, we have ourselves become detectives.

Willa: That’s an interesting way of looking at this, Nina. And those layers of mystery seem to telescope within one another. What I mean is, the private detective – if that’s what he is – really doesn’t seem that interested in what happened or whether the main character is guilty or not. He just wants to catch him on film in a compromising position. That’s his job and he’s trying to do it.

Then we as an audience are a little closer in. We do care about the main character and we do want to know what happened and why, so we’re trying to piece together “the scattered clues,” as you say. We have “become detectives” as we try to construct a narrative that makes sense.

And then there’s the main character himself, who’s even closer in – so much so that in some ways the story of Billie Jean all seems to be playing out inside his own head. It’s like he’s obsessively retelling the story over and over again in his mind, as people tend to do after a traumatic event. I mean, how many times does he repeat the line “Billie Jean is not my lover” or “The kid is not my son”? It’s almost like he’s trying to convince himself that he isn’t culpable somehow. Even if he isn’t legally obligated to provide for her baby, there seems to be an emotional connection to the child whose “eyes looked like mine,” and he seems to be working through that as he replays the story of Billie Jean over and over again.

Nina: That’s a great point, Willa. There’s a persistent disavowal of his relationship with this particular woman and child through the chorus, which carries the song’s main theme.

In the last part of the film, we hear the instrumental break with its punchy guitar riff, as the film cuts to another space. We are no longer beside the huge billboard on the ribbon of sidewalk. Between two dilapidated brick buildings, we are with Michael in an enclosed stairwell that has a somewhat claustrophobic feel.

Willa: Which seems to be a fairly accurate reflection of his psychological state at that point.

Nina: I think so, Willa. Through the lyrics especially, he has already given us a good idea of how he was entrapped or enclosed – with seemingly no way out – by “schemes and plans” that are not of his own making.

A window prominently shows us a neighbor – a woman sitting at a table right next to the window of the adjoining building, with a red phone before her. We see several quick inserted shots, where Michael spins in this small space. His “heeeeess,” which periodically interrupt the guitar riff, are precisely timed to each of his spins.

Willa: Oh, you’re right! I hadn’t noticed that before.

Nina: I don’t know whether it was planned in advance or created in the editing process, but that kind of synchronous moment recalls the one earlier in the film, when Michael’s footfalls on the lit-up squares were timed to the rhythm of the song. It’s a powerful editing device.

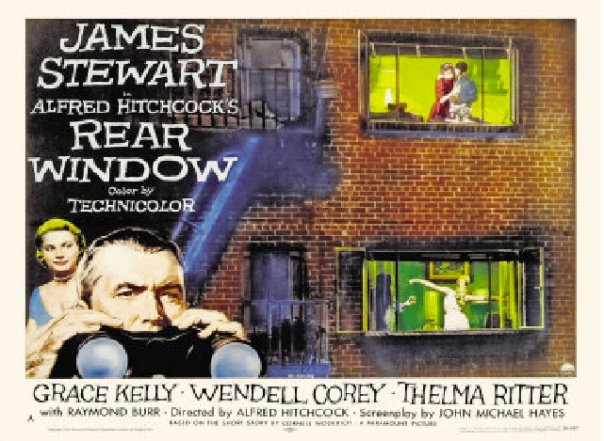

And the image of the woman in the window, as seen from outside, distinctly reminds me of Alfred Hitchcock’s 1955 film, Rear Window. Here are a couple of movie posters:

In Rear Window, L. B. “Jeff” Jeffries (James Stewart) is a professional news photographer who’s temporarily disabled; he’s in a wheelchair with a broken leg, an injury he sustained on his last assignment. Since he has too much time on his hands and is more or less in an immobilized condition, he cuts his boredom and entertains himself by spying on his neighbors, whose activities across the courtyard he can readily view through his apartment’s big picture window – which functions, for him, as a kind of movie screen. Here’s his view of a newlywed couple:

And the courtyard at dusk:

Willa: Interesting! This image of the courtyard, especially, is very evocative of Billie Jean, isn’t it? It’s the same sort of dead-end alley where Michael Jackson’s character goes to climb the steps to Billie Jean’s room.

And here’s a screen capture of the scene you were just describing of the older woman with the red phone seen through the window – the woman who later calls the police:

That could easily be a frame from Rear Window, couldn’t it?

Nina: Yes, they both evoke a very similar atmosphere and a sense of illicit looking – even though this window is closer to us than the neighbors’ windows in Rear Window, which are clear across Jeffries’ courtyard, maybe a hundred feet away.

Willa: Yes, there’s a strong feeling of intimacy in Billie Jean, and maybe that sense of intimacy, even in public spaces, is part of what makes this seem like a psychological journey – that we are inside his mind as much as inhabiting a physical space.

Nina: Yes, Willa. To name one thing, he draws his story from memory, and how can anyone gainsay that? We must identify with him, subjectively. Because he narrates, and because we see so many lingering closeups on his face (and no one else’s), because we share his emotional life on these levels, and because, as Michael Jackson, he comes to the whole scenario with the kind of star power that “needs no introduction,” we can develop very strong bonds of identification with his character, even if this character’s life situation is in no way comparable to ours.

Willa: That’s true.

Nina: Yet Michael’s gesture to the woman on the other side of the window, with her red phone and table fan, wearing something on her head that looks something like a shower cap, gives me a moment of discomfort. It’s as if some contract regarding privacy has been breached, because our sense of decorum in a city requires that a pedestrian and a resident – on opposite sides of a window – not acknowledge each other. By gesturing this “sh ush” to a stranger in her own apartment, Michael leads us to a different kind of space where conspiracy and secrecy replaces anonymity and invisibility. He is asking her not to “give him away” or reveal his presence there. According to some established social conventions, when you live in a congested city, there ought to be an implicit agreement to maintain an illusion of privacy. When you pass by an open window on the street, for instance, you are not to look in. Even if you spot a person “parading around naked” (as the saying goes), and even if some kind of sexual encounter is taking place, you are to keep walking and pretend you haven’t seen anything. (Even if they were to witness a violent crime taking place in an apartment, many people prefer just to keep their noses clean and walk past as if nothing had happened.)

ush” to a stranger in her own apartment, Michael leads us to a different kind of space where conspiracy and secrecy replaces anonymity and invisibility. He is asking her not to “give him away” or reveal his presence there. According to some established social conventions, when you live in a congested city, there ought to be an implicit agreement to maintain an illusion of privacy. When you pass by an open window on the street, for instance, you are not to look in. Even if you spot a person “parading around naked” (as the saying goes), and even if some kind of sexual encounter is taking place, you are to keep walking and pretend you haven’t seen anything. (Even if they were to witness a violent crime taking place in an apartment, many people prefer just to keep their noses clean and walk past as if nothing had happened.)

But many breaches of personal space and privacy occur all the time, beyond anyone’s control. You may sense at times that you’re living in a fishbowl where constant surveillance is your daily lot, while at the same time you are chafing under the anonymity that city life often imposes, which can provide a kind of shelter from constant monitoring but at the same time denies you the fame and notoriety you may desperately want! Those contradictions, I think, formed a large part of Michael Jackson’s life. And both Billie Jean and Rear Window are largely about blurring the distinctions between the public and the private.

Willa: That’s really interesting, Nina. And it’s true that the boundary between public and private was a fraught one for Michael Jackson – one he was constantly trying to negotiate as he dealt with that odd mix of isolation and exposure brought on by celebrity. So it’s interesting to see how that boundary between public and private is breached and redrawn in both of these films.

Nina: Yes, and it’s also telling that the staging of these stories required a sealed, private environment: both films were shot on a film set (an enclosed, controlled space), and not on location.

Jeffries is housebound, and he is increasingly fascinated by the activities he sees. He can enjoy a sense of power through his ability to control other people by narrativizing them: he makes up stories and even invents nicknames for them. First with a pair of binoculars, and then the long telephoto lens of a camera he uses for his professional work, he concocts fantasies about his neighbors’ lives as he peers into their curtainless windows. He finally becomes an amateur detective himself: his prosthetic “eyes” allow him to discover a possible murder and cover-up as he stares, transfixed, at the windows across the courtyard. The following stills show us Jeffries and the apparatuses he uses:

And then “reverse” shots that disclose his point of view, such as this shot of Mr. and Mrs Thorward:

And this one of Mr. Thorwald, a potential murderer:

And this one of a neighbor he calls “Miss Lonelyhearts”:

Willa: And again, these images are evocative of Billie Jean. For example, in this last movie still, there’s the dark brick wall outside and the well-lit space inside so that, ironically, what’s inside is more visible than what’s outside – just like the apartment of the woman with the red phone in Billie Jean. We can barely make out the bushes, gutter pipe, and iron railing outside, but we can see every detail of “Miss Lonelyhearts” preparing a romantic table for two.

So in some ways, Jeffries is like us as we “narrativize” the images we see in Billie Jean and try to form them into a story. But in other ways, he’s more like the detective character. He’s a photographer and he intrudes into other people’s private lives – just like the detective in Billie Jean – without their knowing it.

Nina: Yes, that’s true, I think – Jeffries combines both kinds of obsessive looking. What he’s up to seems sleazy, and several people in his life urge him to stop his near-obsessive spying (including his girlfriend, who at one point tells him his behavior is “diseased”). As it turns out, however, he is vindicated in the end, since his spying was instrumental in uncovering a criminal act.

Willa: He’s vindicated because his “looking” allows him to bring a murderer to justice?

Nina: Well … He starts out “spying” as a distraction, to pass the time. But then he discovers something untoward happening in an apartment across the courtyard. I won’t give away too much here, but everyone should really see this film! It’s one of the classics of the “suspense thriller” genre, which Hitchcock was especially known for.

Willa: You’re really making me want to see it again, Nina. To be honest, I haven’t watched it since I was a teenager (about 40 years ago!) so a lot of the plot details are pretty fuzzy. I do remember having contradictory feelings about Jimmy Stewart’s character, and agreeing with Grace Kelly’s character about his obsessive watching.

Nina: Rear Window has been very thoroughly studied by film critics and scholars for decades now because it so perfectly illustrates how our own physical and psychological state as film spectators are akin to Jeffries’, and especially when we view films on the big screen at the theater. We are more or less immobilized in our seats, as he is in his wheelchair, and we’re peering into a world that’s displayed before us, gazing at a screen that reveals people in their most private moments: moments that maybe we’re not “supposed” to be seeing. By all rights, we should be embarrassed by this “guilty pleasure,” but of course that’s the whole appeal of the film spectacle. Why would we give up a position where we have the distinct privilege of seeing everything that’s going on through an omniscient camera? We never get that chance in real life!

And so, it can be said that we become voyeurs every time we see a movie, just as L.B. Jeffries, watching his window as if it were a movie “screen,” is a classic voyeur in Rear Window.

Willa: Oh, interesting! And of course, that plays out at both levels in Billie Jean as well. There are the repeated scenes of voyeurism within the film, as you’ve been pointing out (the detective with his camera obviously, but also the main character himself looking at the panhandler, or looking at the woman with the red phone, or looking at Billie Jean lying in her bed) and also outside the film, as we as an audience watch the video and piece together the clues we’re given into a story.

Nina: That’s true, Willa. And yet, maybe because Billie Jean is a music video, or because it’s short (as music videos tend to be), or because it’s Michael Jackson, this main character’s mode of voyeurism seems somehow less sinister, because he’s looking at things without the intermediary of binoculars, a camera, or (usually) a window. The people he sees can see him, too.

Still, it turns out that Billie Jean’s way of telling a story and revealing information is almost as cagey as Michael Jackson himself could sometimes be! There’s allusion and implication, rather than disclosure of facts (but isn’t that’s what many works of art are about, anyway; since they’re built on metaphor)? But while most films noir assure us that we will learn the “answer” to the puzzle in due time, in Billie Jean (as in the ongoing saga of Michael Jackson’s life), while more disclosures are promised, and while we eagerly await the definitive “solution” to a riddle or mystery, the answer, of course, never arrives.

But in the end, as we watch Billie Jean – and as we regard Michael Jackson with the kind of fascination reserved for larger-than-life figures – we (or, speaking for myself here, I) am again left with a set of vexing questions about Michael himself. I’m revisiting these questions for the umpteenth time, knowing that I will never find an answer, but compelled by the process of investigation itself. Like Rod Riley and his mysterious disappearing man, I ask again and again, “the guy was trying to tell me something. But what?” I think many of us feel this way. We’re MJ sleuths.

There are many parallels, I think, between Rear Window and Billie Jean, on the thematic as well as the visual level. For one thing, there is a tradition in cinema where photography is a major motif, and photographers play a pivotal role in solving crimes … or in committing them. Here I’m thinking of Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blowup (1966), where a fashion photographer becomes a reluctant hero-detective; or Peeping Tom, a psychological thriller (1960) by British director Michael Powell, where an amateur-style movie camera assists a young man’s killing spree.

I’m also thinking of photography’s role in divorce cases (based on some old-school detective work) where the goings-on of “cheating” husbands and wives can be recorded as evidence. Here I’m thinking of Maurice Chevalier’s role as a Parisian detective in Love in the Afternoon, with Audrey Hepburn and Gary Cooper, from 1957, which is also the stuff of Hollywood romantic comedies from the 1930s through the 1960s. And so, what immediately came to my mind when I first started thinking about Billie Jean, was that the lyrics alone might imply a paternity suit; and a few music critics I’ve read believe that’s where things are heading in the story of Billie Jean as retold by Michael, the “narrator.”

Willa: I think so too – especially with the lines, “For forty days and forty nights / The law was on her side.” That implies there’s a lawsuit involved in her “claims that I am the one” who fathered her son. So maybe the detective has been hired to support her claims.

Nina: Yes, It would seem so, Willa; at least that’s a good possibility. It seems cryptic – but again, prescient in terms of Michael Jackson’s legal battles.

You also had an intriguing idea last time we posted, Willa, about how the man in the trenchcoat may be a detective (in the old-fashioned film noir sense), and also a more present-day kind of paparazzo. That made me think more about Michael’s many real-life encounters (pleasant and not) with photographers. And of course this bears directly on Billie Jean, as well as the first few moments of You Are Not Alone, where we see an intense display of flashbulbs going off as Michael walks slowly past a huge crowd of reporters, while singing, “Another day is gone / I’m still all alone.” An ordinary day for Michael Jackson is a day in which thousands – or tens of thousands – of photographs have been taken of him. “All in a day’s work.”

Willa: Yes. We see depictions of paparazzi in Speed Demon also, and as in Billie Jean, it ends with them getting hauled off to jail by the police. But that doesn’t mean the police are on Michael Jackson’s side – they may help him at times, but they’re a potential threat also, and so he tries to elude them as well. So there’s a constant three-way tension between him, the photographers who pursue him, and the police.

Nina: Yes, Willa, now that you mention it, his tormenters in Speed Demon are carted away by the police, while Michael goes free, thanks to his power to transform (or “disappear”) himself.

And speaking of the representation of paparazzi in more recent films, I recent came across an article by Aurore Fossard-De Almeida, “The Paparazzo on Screen: The Construction of a Contemporary Myth.” According to Fossard-De Almeida, those who practice within this relatively new profession are pure products of contemporary tabloid culture. Unlike the classic detectives of old, like Sam Spade, or Philip Marlowe, or the one-off “Rod Riley” (quasi-heroes who had smarts, integrity, and charm underneath their gruff exteriors), these guys are thoroughly despicable characters with no redeeming qualities whatsoever. They have no interest in seeing justice served.

Detectives’ work serves to uphold the law and establish “truth and justice”; therefore they have the moral high ground, even with their cold personalities and unscrupulous methods. Paparazzi’s only function in society, however, is to make a great deal of money by selling their bounty to publications whose main appeal is to the baser instincts of a public obsessed with celebrities and their downfall. Either way, this pursuer cannot be caught looking. In Billie Jean, the detective skitters around in the street, runs around corners, flattens himself against buildings. He must not be detected; and so he tries to make himself invisible, just as Michael has done, but without Michael’s superlative magical powers.

His success lies in apprehending or photographing his suspect/subject without attracting his or her notice. He should be able to watch the person while remaining out of range of any reciprocal watching: that’s his whole currency. As an amateur “sleuth,” L.B. Jeffries has to maintain his own invisibility; it’s also the key characteristic of the classic voyeur. So the detective, in his role as a paparazzo, becomes a voyeur. Michael Jackson also stands at the window of an apartment (Billie Jean’s room, we assume), looking in. He is also a voyeur, but of a less sinister kind. As the focus of our sympathy and identification (and, for many, desire), and as the object of our collective “gaze,” we might admit that “he was more like a beauty queen from a movie scene.” His distinct advantage – the ability to become invisible – is one key to his numinous beauty: in some way, we might regard him as a disembodied, pure spirit.

Willa: Which would answer in an unexpected way the central question of the song. A spirit can’t father a child since it takes a body to reproduce a body. So if it’s true that he’s disembodied, then it must also be true that “Billie Jean is not my lover.” And this interpretation is supported by the scene where he climbs into her bed and then disappears – the sheet falls flat as he dematerializes.

But he isn’t purely spirit, I don’t think. At times he seems very embodied! To me, it seems more accurate to say that he’s ever-changing – like a conjurer he can seemingly shift at will and make himself invisible or immaterial. There are also times when he’s both – when he’s invisible yet seems to have material weight – like the two scenes near the end when he isn’t visible but yet the pavers light up under his weight. So in those final scenes, he is both present and absent – material yet invisible.

Nina: Yes, I think that’s true, Willa: a conjurer is a good way to put it. And an invisible man can still have a tangible body, and even impregnate somebody: I’m sure Gothic fiction is filled with such strange occurrences!

Willa: Yes, and so is Greek and Roman mythology, and the New Testament of the Bible. I mean, that’s the miracle of the immaculate conception …

Nina: At another level, Michael’s actions in the film hint at some intangibles that, in many ways, echo his life. In Billie Jean he can “dematerialize” in order to shield himself from the prying eyes of either the law, the detective, neighbor, the photographer, but he also excelled – across his whole body of work – in making the invisible visible.

Ever since he started performing as a child, his presence as a visible force in an industry that thrives on both intense exposure (the “star system”) and secrecy, enabled him to bring some hidden practices to light. His own sacrifices to an industry that created and destroyed him served as an allegory about what happens to other children who take on the burden of too much responsibility at too young an age. The exploitation of child labor was a consistent theme of his, central to the ways he narrated his life in interviews, etc. Perhaps the ways he exposed this issue and others, was the “crime” for which he paid; some people may have feared that he was about to “blow the whistle.” But, to paraphrase Riley’s question: “blow the whistle” on what?

Willa: That’s an interesting point, Nina. He also forced us to confront some of our most intractable social problems – racism, misogyny, child abuse, war and police brutality, hunger and neglect, and other “invisible” crimes – and in doing so made them highly visible, as you say. For example, his mere presence in Dona Marta in the Brazil version of They Don’t Care about Us brought global attention and improved conditions there. As Claudia Silva of Rio’s office of tourism told Rolling Stone,

This process to make Dona Marta better started with Michael Jackson. … There are no drug dealers anymore, and there’s a massive social project. But all the attention started with Michael Jackson.

We see subtle hints of him making the invisible visible as he climbs the steps to Billie Jean’s room. Each tread lights up as he steps on it, and the letters of the vertical “HOTEL” sign illuminate one by one as he rises to their height. So his mere presence makes them highly visible.

Nina: I agree, Willa: the work he did in Brazil, for example, kind of gives new meaning to the expression, “shedding light.” And he did shed light on some realities that some highly placed people would probably rather stay covered.

Besides The Band Wagon, Billie Jean pays a more-or-less direct homage to another musical by Vincente Minnelli: An American in Paris, with Gene Kelly and Leslie Caron (1950).

I became aware of this because in September 2009, the University of California at Berkeley held a one-day conference called Michael Jackson: Critical Reflections on a Life and a Phenomenon. One presentation, by Ph.D. student Megan Pugh (“Who’s Bad?: Michael Jackson’s Movements”), pointed to a strong visual comparison between the sequence in Billie Jean where each stairstep lights up, and a musical number called “I’ll Build a Stairway to Paradise” that appears in An American in Paris. (The stairway sequence begins at 1:00):

The song was written by George Gershwin (who in fact wrote all the music in An American in Paris), and was first recorded by the “King of Jazz,” Paul Whiteman and His Orchestra, in 1922:

All you preachers

Who delight in panning the dancing teachers

Let me tell you there are a lot of features

Of the dance that carry you through

The gates of HeavenIt’s madness

To be always sitting around in sadness

When you could be learning the steps of gladness

You’ll be happy when you can do

Just six or sevenBegin today!

You’ll find it nice

The quickest way to paradise

When you practice

Here’s the thing to know

Simply say as you go…Chorus:

I’ll build a stairway to Paradise

With a new step every day

I’m gonna get there at any price

Stand aside, I’m on my way!

I’ve got the blues

And up above it’s so fair. Shoes

Go on and carry me there

I’ll build a stairway to Paradise

With a new step every dayAnd another verse:

Get busy

Dance with Maud the countess, or just plain Lizzy

Dance until you’re blue in the face and dizzy

When you’ve learned to dance in your sleep

You’re sure to win out

This is kind of the obverse of Michael’s simultaneous singing and dancing in Billie Jean, where he tells us how risky it can be to “dance on the floor in the round.” (“So take my strong advice / Just remember to always think twice.”)

People often frequent dance clubs when they’ve “got the blues”; they go in the hopes that dancing will help them transform their ill mood into something rosier. So much pop music, through the ages, has brought out the possibility of cheering up, of “losing your blues” through dancing. Of course, Michael Jackson himself often sang these kinds of songs as lead singer of the Jackson 5 and The Jacksons, as well as in his adult solo career. There’s “Keep on Dancing” from The Jacksons first album in 1976, with Michael singing lead:

Dancing, girl, will make you happy

And happy is what you want to be

Dancing fast, just spinning around

Dancing slow when you get down

Keep on dancing … let the music take your mind

Keep on dancing … and have a real, real good time

Keep on dancing … why don’t you get up on the floor

Keep on dancing … ’til you can’t dance no more

“Enjoy Yourself,” from the same album, is another example, with Michael singing lead:

You, sitting over there, staring into space

While people are dancing, dancing all over the place

You shouldn’t worry about things you can’t control

Come on girl, while the night is young

Why don’t we mix the place up and go! Whoooo!

By all rights, Michael’s wingtip shoes should have “carried him” away from his blues when he first met Billie Jean on the dance floor. Interestingly, the idea of dancing as a way to escape your woes, has turned to its opposite with the Thriller album in 1983, where “dancing” may result in misery. Some shift has taken place, even since 1979’s “Off the Wall” where dancing is still a harmless pastime that’s connected with achieving happiness (“Rock With You,” “Get on the Floor,” “Off the Wall,” and “Burn This Disco Out”).

What has happened, I wonder? We can blame it on the boogie, but it would seem that dancing itself can no longer be seen as a straightforward matter, and can be read as a euphemism for a sexual encounter: in this instance having unexpected, tragic results. On the album, “Billie Jean” and even “Wanna Be Startin Something” (“you’re a vegetable, they eat off you, you’re a buffet”), are the two tracks that several writers believe to have marked the initial stages of a “paranoid” tendency in Michael’s songwriting: and in their view, this tendency would become more prominent in his later albums.

And so, in Michael’s fateful encounter with Billie Jean – a girl he apparently picked up and casually bedded after meeting her for the first time at a club – dancing didn’t remove his unhappiness, but deepened it. Throughout the film, his demeanor is somewhat despondent: he sighs, frowns, and sings lyrics about how he rues the day he and Billie Jean first “danced.” Nevertheless he is about to reenact, before our eyes, the same error that initially brought him to this regrettable state, as he spins in Billie Jean’s garbage-strewn, graffiti-ridden stairwell.

Willa: Hmmm … That’s really interesting, Nina. I’m not sure that the main character “bedded” Billie Jean – I think that’s left pretty indeterminate, with contradictory clues – but it is true dancing has taken a sinister turn in “Billie Jean” that we haven’t seen before. I’m quickly running through Michael Jackson’s albums in my mind, trying to think of other songs where dancing leads to misery. There’s “Blood on the Dance Floor,” of course – but in many ways that song feels to me like a retelling of “Billie Jean,” so it makes sense they would share that connection.

Nina: Yes, that’s a good point; I also wonder if any other songwriter has written such a tale of woe about dancing.

Michael’s ascension of the back-alley staircase in this “slum” dwelling (as we might describe it) of course contrasts hugely with George Guétary’s opulent fantasy staircase, with its glamorous showgirls and ornate candelabras. Michael’s character will surely not “win out,” nor will he find any stairway to “paradise” or “heaven” (Led Zeppelin) through his dancing – only his divided self, a guilty conscience, and a compulsion to return to the sordid scene of his “downfall.” Instead of finding (or building) paradise, he seems to fear he’ll be sent in the opposite direction. But he dances and goes upstairs anyway.

As Megan Pugh observes,

Jackson zooms between a longing for the dreamworld of Hollywood Musicals – where you can solve problems by putting on a show, where boy gets girl, and where everything ties up neatly – and the realizations that such dreams may not be attainable. For in the end, Jackson almost always ends up alone.

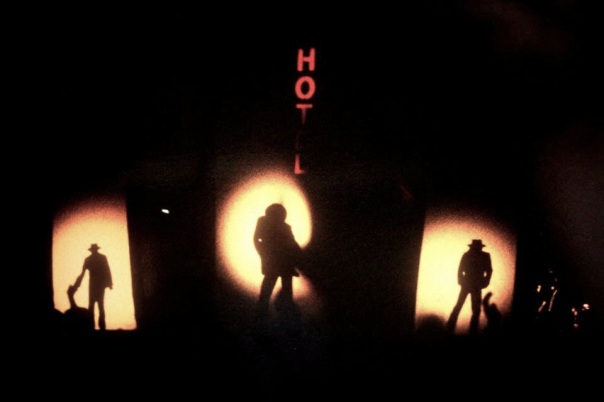

As he lights up each step, the neon sign “HOTEL” is also lit, one letter at a time. This HOTEL sign became a regular feature of Michael Jackson’s concerts, when he performed as a silhouette behind a screen that accentuated the sharpness of his moves. It was used as an introduction that preceded either “Smooth Criminal” or “Heartbreak Hotel” on the Bad tour.

Willa: Wow, that’s fascinating, Nina! Here’s a clip of “Smooth Criminal” from Wembley Stadium in 1988, and we can clearly see the neon “HOTEL” sign with the red letters arranged vertically. It’s just like in Billie Jean, but I hadn’t made that connection before.

As it says in the voiceover,

My footsteps broke the silence of the predawn hours, as I drifted down Baker Street past shop windows, barred against the perils of the night. Up ahead a neon sign emerged from the fog. The letters glowed red hot, in that way I knew so well, branding a message into my mind, a single word: “hotel.”

So he draws our attention to this “red hot” hotel sign both visually and aurally, suggesting it’s an important element for him.

Nina: Yes: and thanks, Willa! I’ve often wondered what was being said there, but I never heard the words on a good sound system. So here we have an idea of the “red hot” letters branding our protagonist’s mind – like a mental stigmata – along with certain “perils of the night,” and his musings that he knew these red letters “so well.”

By this account, then, our hero seems to be taking us on an imaginary journey to the “red light district” of the city, where his memory reveals his repeated visits to a certain house of ill-repute.

“The House of the Rising Sun,” a song that was recorded by just about everybody, was made most famous by The Animals in the 1960s. Here are some lyrics that are used in another version, recorded by a woman:

There is a house in New Orleans

They call the rising sun

It’s been the ruin of a many a poor girl

And me, oh god are one

If I had listened like mama said

I would not be here today

But being so young and foolish too

That a gambler led me astray

Again, we have a mother whose advice to her child went unheeded, as it did in Billie Jean:

And mother always told me

Be careful who you love

Be careful what you do

’Cause the lie becomes the truth

The many recorded versions of “House of the Rising Sun” reveal the song’s storied history, where the “house” is sometimes (most obviously) a bordello in New Orleans, a women’s prison, or a nightclub that serves as a gambling den, among other kinds of places. Nowhere in “Billie Jean” do we have the sense that she is a prostitute, but there are some common themes in those lyrics, such as giving in to temptation, experiencing remorse, and being “led astray” by an unscrupulous lover.

This places the story of “Billie Jean” in a folk-blues-country tradition, where there are so many songs that impart this message: you disregard your mother’s wisdom at your own peril. Another example is “Hand Me Down My Walking Cane,” of which countless versions have been recorded, many with different lyrics and in different musical styles.

Hand me down my walking cane

Hand me down my walking cane

Oh hand me down my walking cane,

I’m gonna leave on the midnight train

My sins they have overtaken me.

If I had listened to what mama said

If I had listened to what mama said

If I had listened to what Mama said

I’d be sleepin in a feather bed

My sins they have overtaken me

I’m sure there are many, many other examples.

Willa: Yes, there really are. One that immediately springs to mind is the old Merle Haggard song “Mama Tried,” with this attention-grabbing chorus:

I turned twenty-one in prison doing life without parole

No one could steer me right but Mama tried, Mama tried

Mama tried to raise me better, but her pleading I denied

That leaves only me to blame ’cause Mama tried

Nina: Oh yes, that song was in the back of my mind, but I couldn’t quite place it! Thanks for reminding me, Willa. Michael Jackson clearly absorbed and understood these songs and their themes, whether or not he consciously inscribed them into his lyrics. In some ways, we might say that he re-wrote some traditional songs in ways that could later be recognized as the timeless folk songs of a new generation. (Although it’ll be a LONG time before his compositions pass into the public domain!)

As for the vertical “HOTEL” sign, here’s one that’s beautifully photographed in black-and-white with window reflections:

This still is from the 1946 noir film, Murder, My Sweet, directed by Edward Dmytryk. Here, Dick Powell (an actor and singer who is best known for his roles, a decade earlier, in a series of depression-era musicals) – appears as hard-boiled detective Philip Marlowe. It’s possible that Michael Jackson, or Steve Barron, or another person involved in the production of Billie Jean, drew from this image – which had been “branded” indelibly into their mind.

As we were saying in an earlier post, according to AMC Filmsite commentator Tim Dirks on the film noir genre, these films often featured

an oppressive atmosphere of menace, pessimism, anxiety, suspicion that anything can go wrong, dingy realism, futility, fatalism, defeat and entrapment.… The protagonists in film noir were normally driven by their past or by human weakness to repeat former mistakes.

Michael’s predicament in Billie Jean readily fits several of these elements. As we’ve discussed before, he implies that he was driven by “human weakness.”

People always told me be careful what you do

Don’t go around breaking young girls’ hearts

But she came and stood right by me

Just the smell of sweet perfume

This happened much too soon

She called me to her room