Rereading Michael Jackson

This article was written by Willa and summarizes some of the ideas presented in M Poetica: Michael Jackson’s Art of Connection and Defiance. It was published by the Michael Jackson Fan Club in July 2011, and has been reposted here by permission.

During the late 1980s and early 1990s, a startling cultural phenomenon transfixed the nation and the world: Michael Jackson seemed to be “turning white.” By the mid-1980s, Jackson was arguably the most famous man in the world. And then, with the whole world watching, he gradually altered the physical signifiers of his race right before our astonished eyes. It was unimaginable, as if he had sprouted wings. People simply could not believe it, and they could not stop talking about it.

I was going to graduate school in the South and it seems like every class, at least once during the semester, turned into a Michael Jackson discussion group. It didn’t matter if the class was supposed to be about Cavalier poets or Transcendentalists or British women novelists — at some point in the term we’d get into a Michael Jackson debate that would completely take over the class discussion. I saw it happen again and again. Students and professors alike, as well as the nation at large, could not stop talking about the changing color of Jackson’s skin, and how to interpret it, and how to react, and what it meant culturally.

And we’re still talking about it. Twenty years later, the changing face of Michael Jackson still challenges us, forcing us to confront some of our deepest, most repressed feelings about race and identity.

Typically with a cultural event of this magnitude, there is a wide range of opinions regarding underlying causes. Yet with this particular phenomenon, there doesn’t seem to be. With the possible exception of Jackson’s fans, it is generally agreed that he changed the apparent color of his skin and other racial signifiers because of deep insecurities and his own inner demons. Yet, if we look closely at his work and his life, Jackson himself suggests a very different interpretation: that it was an artistic decision.

For example, in his Scream video, released in 1995, Jackson’s character considers three images. The first is a portrait of Andy Warhol, who suffered from auto-immune disorders as a child — disorders that attacked the pigment of his skin — and later developed an eccentric public face as part of his art: extremely pale skin, jet black eyebrows, and a series of raggedy white wigs. The third is a René Magritte painting, The Son of Man, in which a still life, a work of art, has been superimposed over the subject’s face: we see art where we expect to see a face. Between them is an abstract by Jackson Pollock, whose first name gains significance in this context. It functions like an arrow, telling us which way to look as we interpret the two adjacent images. Jackson reinforces this idea by cutting to his own image before returning to the Pollock painting. Through the careful selection and placement of these images, Jackson uses the language of art to explain that, like Warhol, his changing appearance began as a medical condition that attacked his pigment cells, but it became a deliberate artistic decision.

Jackson’s conversations with his dermatologist, Dr. Arnold Klein, support this interpretation. Dr. Klein has confirmed that Jackson suffered from vitiligo, but he has also said that Jackson repeatedly discussed his face as “a work of art.” For example, in a November 5, 2009, interview, Klein said, “You have to understand. It’s hard to … understand this, but he really viewed his face as a work of art, an ongoing work of art.”

There are other, more subtle indicators as well, the most important being that Jackson never showed any excessive ambivalence about his race. Instead, we see his obvious pride at being considered an heir to James Brown and part of a long tradition of black performers, and we see his work with younger artists such as Lenny Kravitz, Will.i.am, Akon, Usher, Ne-Yo, and many others, including young hip hop artists. Producer Teddy Riley, who worked with Jackson on his Dangerous, Blood on the Dance Floor, and Invincible albums, says,

Of course he loved being black. We’d be in sessions where we’d just vibe out and he’d say, “We are black, and we are the most talented people on the face of the Earth.” I know this man loved his culture, he loved his race, he loved his people.

We also see his support for causes such as the NAACP, the United Negro College Fund, the Congressional Black Caucus, the National Rainbow Coalition, and relief efforts for Africa. And listening to interviews over the years, the ones where he seems most truly at ease are his interviews with Ebony, such as his last interview in November 2007 where he’s engaged and laughing and having fun. All of this leads to the conclusion that if Jackson’s appearance hadn’t changed, we probably never would have questioned his racial identification. Discomfort with his race simply wasn’t an obvious part of his psychological make-up.

There are other indicators as well. For example, there’s his advice to Kobe Bryant, who has called Jackson his mentor, that “it’s OK” to push yourself and your profession to an extreme in pursuit of an ideal:

One of the things he always told me was, Don’t be afraid to be different. In other words, when you have that desire, that drive, people are going to try to pull you away from that, and pull you closer to the pack to be “normal.” And he was saying, It’s OK to be that driven, it’s OK to be obsessed with what you want to do. That’s perfectly fine. Don’t be afraid to not deviate from that.

And there’s a funny little anecdote Stevie Nicks tells from Bill Clinton’s inauguration. She and Jackson were performing at Clinton’s inaugural concert, and Jackson asked through an aide if he could borrow some makeup. She sent it over, but it came back unused. “I was using a light Chanel foundation. . . . Michael sent back a note to say thanks, but the shade wasn’t light enough for him.” This story just makes me shake my head and laugh. It simply isn’t the action of an insecure black man trying to pass as white and hoping no one will notice. Rather, it strikes me as the work of a trickster — of a confident artist with a sly sense of humor, trying to make a point.

But what was that point? If we accept that Jackson’s changing face was art, as he told Dr. Klein and suggests in Scream (and Ghosts and Black or White) what does it mean? How do we interpret it? Perhaps the best way to approach this is to look at the effect it had. Bill Clinton repeatedly said he wanted to start a “national conversation about race,” but even with the power of the presidency behind him he was never able to make it happen.

Michael Jackson did, and took it global. In fact, we couldn’t stop talking about race, or stop thinking about it. Every time coworkers gathered around a copy machine and mocked him for “turning white,” or every time a parent corrected a child and said, no, he’s not a white woman but a black man, at some level they had to stop and think about what those labels mean. What does it mean to be black, or be white? What does it mean to be masculine, or be feminine? Every time Jackson called himself a black man — as he unwaveringly did, even when his face was as white as a geisha’s — we had to stop a moment and think about it. What does that mean exactly, and why is it so important to us? Every time we looked at him, we experienced the weird dissonance of our eyes disagreeing with our brains, forcing us to question beliefs we thought we knew to be true.

Jackson understood the exquisite power of that dissonance, and he knew precisely how to create and sustain it. He never let us forget the changing color of his skin. In fact, he made sure it stayed in the foreground of our perceptions of him. He varied his look constantly so we could never grow accustomed to his appearance, and he often used makeup that was startlingly white — not the shade he would have chosen if he were trying to pass unnoticed.

But he didn’t want to “pass.” That wasn’t his purpose. His goal was just the opposite. When people of color try to pass, they hope no one will notice the color of their skin. Jackson forced us to notice, and forced us to deal with it — forced us to deal with the shame and anger, the arrogance and contempt, the many subterranean feelings about race his changing face brought to the surface. Jackson didn’t want us to get comfortable with the changing color of his skin, didn’t want us to stop feeling the conflict within ourselves when confronted with that change, and didn’t want us to stop thinking about the implications of that conflict and why we feel it so strongly. And we haven’t. After two decades and even after his death, we still feel that conflict inside ourselves, we still talk about it, and it still challenges us.

It’s important that Jackson chose to disrupt the signifiers of gender as well as race, since our reaction to each illuminates the other. While many people accused him of being ashamed of his race, no one accused him of being ashamed of his gender. His shifting of signifiers in terms of race and gender were similar, but our reactions were very different. So was the difference in him, or in us? Was he ashamed of being black, or were we so insistent on interpreting him that way — even after he told us he had vitiligo — because we still see something shameful about being black in ways we don’t see anything shameful about being male? These are the kinds of unsettling questions that Michael Jackson, the artist, forces us to confront within ourselves.

Perhaps the effect on children has been even more profound. My 12-year-old immediately recognizes Jackson in everything from “ABC” video clips to Beat It to Men in Black II, and he seems perfectly comfortable with the idea that one person can look so different yet be so uniquely and obviously himself. Michael Jackson, both as a person and a concept, simply makes sense to him in ways I don’t quite understand.

This leads me to wonder about the entire generation of kids who’ve now grown up with the many faces of Michael Jackson. I wonder if somehow they designate “being black” and “being white” less rigidly than previous generations — if their perceptions of racial boundaries are somehow more fluid and less absolute—all because one man had the vision and courage to cross those boundaries.

And it did take courage. The pressures on Jackson to conform must have been tremendous — from his supporters as well as his detractors, blacks as well as whites. No one liked what he was doing. But he defied us all and did what he wanted or needed to do. If the goal of the artist is to unsettle us, to challenge our perceptions and beliefs and force us to see ourselves and our culture in new ways, then Jackson’s most provocative work of art was arguably his own evolving body. While Warhol forced us to look at Campbell soup cans and think about our relationship with consumer culture in a new way, Jackson forced us to look at him — the little boy we’d loved since childhood who grew up into something unexpected — and challenged our assumptions about identity and race, gender and sexuality.

“Am I the Beast You Visualized?”

But as we’ve seen with visionaries from Socrates to Galileo, William Tyndale to Charles Darwin, you can’t defy such deeply held beliefs without consequences. In 1993, at a time when Jackson was challenging our ideas about race, gender, and sexuality most severely — when he was appearing uncomfortably different and unfamiliar to us and therefore was extremely vulnerable to misinterpretation — at this critical moment, the unthinkable happened: a man accused Jackson of sexually abusing his son.

The evidence against Jackson is problematic at best. The father’s intense pursuit of a large cash payoff so alarmed the boy’s mother and stepfather, who became convinced the father was plotting an extortion attempt, that the stepfather began recording their phone conversations. In those conversations, the father admits he has paid people to carry out a “plan that isn’t just mine,” saying, “There are other people involved that are waiting for my phone call that are intentionally going to be in certain positions. I paid them to do it.” He also says, “I’ve been told what to do” and will say “what I’ve been told to say,” and boasts, “If I go through with this, I win big time.”

Eight days after this conversation, the father, who was a dentist, took his son to his dental office, where they were joined by an anesthesiologist who had been asked to leave his previous position because of ethics violations and now made a living doing odd jobs. The father pulled one of his son’s baby teeth and then aggressively questioned the boy about his relationship with Jackson. The father later wrote a chronology based on his memory of events, and his account of that day at the dental office reveals a very disturbing picture.

First, the father begins the conversation by lying to his son, telling him that “I had bugged his bedroom,” when he had not, and “I knew everything,” when he did not. He then fabricates a story that includes explicit sexual acts and tells the boy he knows that he and Jackson have done these things. The father asks his son to repeat this story of sexual misconduct back to him, telling him that “I knew everything anyway and that I just wanted to hear it from him.” He then threatens to destroy Jackson’s career if the boy doesn’t do what he wants, saying that if he doesn’t tell him what he expects to hear, “then I’m going to take him (Jackson) down.”

Based on the father’s own description of what happened that day, it’s clear he questioned his son in a very manipulative and coercive way. However, not only are the father’s words coercive; the whole situation is coercive. Why does he choose to question the boy in his dental office, immediately after pulling out one of his teeth? This, to me, is the most stunning part of the entire story. I would think the father would want to discuss a sensitive issue like this when his son was feeling safe and comfortable and free to talk — not when he was sitting in a dental office, bleeding from a wound his father himself inflicted. There could hardly be a clearer demonstration of parental power, or the father’s ability to carry out his threats and inflict pain. In fact, it’s hard to imagine a more frightening situation for a child than this father’s interrogation of his young son.

However, it’s possible the father had a reason for questioning his son at such an unlikely place and time: because he wanted to question him while he was sedated. In his chronology, the father clearly states that he waited until his son was no longer sedated to raise the issue: “When Jordie came out of the sedation I asked him to tell me about Michael and him.” However, in a KCBS-TV report on May 3, 1994, the father tells a reporter the allegations were made while his son was still under sedation, though he doesn’t answer the reporter’s question about the type of drug used to sedate the boy. If the father’s response to KCBS-TV is true, it is very troubling that the boy first agreed to the allegations while under the influence of some unknown drug, especially given the way the father conducted the questioning: with lies, and threats, and the suggestion of specific sexual acts.

Despite such dubious evidence, the District Attorney’s office aggressively pursued the case against Jackson — and the press and public opinion followed their lead. It’s a valid question to ask if the police (and the press, and the public) were motivated primarily by the evidence or by misreading Jackson’s personality because of his art, because of his transgression of traditional boundaries of race, gender, and sexuality. As Jackson suggests in Ghosts, perhaps the real crime for which he stood accused was being a “freak,” a “weirdo,” and a lot of people seem to have found him guilty on that charge.

“Am I Scary for You, Baby?”

In many ways, Ghosts is Michael Jackson’s most important work. It not only provides interesting insights into Jackson’s analysis of the child molestation case; it also provides a key for interpreting his other work. It articulates Jackson’s artistic vision and philosophy that art should be entertaining yet powerful, even “scary” — in other words, that art should encourage us to question ourselves, our prejudices, and our assumptions in ways that may feel “scary” or threatening or uncomfortable, but that ultimately lead to new insights.

All of this indicates that the song “Is it Scary” from Ghosts must have something very important to say: its title gets to the heart of Jackson’s aesthetic vision. Yet its lyrics are perplexing. Here’s an excerpt:

I’m gonna be

Exactly what you wanna see.

It’s you who’s haunting me

Because you’re wanting me

To be the stranger in the night.

What does that mean? This song was written at a time when public opinion was beginning to shift and solidify in a new way: people were starting to see Jackson as a child molester, a “stranger in the night.” He seems to be referring to public perceptions surrounding the scandal. But what about the lines, “I’m gonna be / Exactly what you wanna see”? What does that mean?

In the following stanzas, Jackson repeats this idea — that he will reflect the ideas we are projecting onto him — and makes it more explicit:

Am I amusing you

Or just confusing you?

Am I the beast you visualized?

And if you wanna see

Eccentric oddities

I’ll be grotesque before your eyes.

Let them all materialize.

What does he mean by that — by “eccentric oddities” and “I’ll be grotesque before your eyes”? And what does he mean by these lines a few stanzas later?

So tell me,

Is that realism for you, baby?

Am I scary for you?

What does that mean? What exactly is he saying?

If I’m interpreting this correctly, I think it means we need to go back and re-evaluate everything we think we know about Michael Jackson’s life after 1993.

“I’m Gonna Be Exactly What You Wanna See”

One of the things we think we know about Jackson after 1993 is that he had extensive plastic surgery — that he was, in fact, obsessed with plastic surgery. Yet those judgments are based on photographs, and when assembling those photographs for comparison, the tabloids invariably pick the most divergent ones, the outliers: in other words, the ones that most vividly support the conclusion they’re trying to prove. But what if we do the opposite? What if we avoid the outliers and compare photos that look more alike? Below is a series of five photos spanning 34 years of Jackson’s life, from his early teens to his late 40s, and except for the nose and chin cleft changes Jackson acknowledged in his autobiography, Moonwalk, in 1988, I see no signs of plastic surgery.

I know very little about plastic surgery, but looking at these photos and more like them, I just see the natural progression of a maturing face. His forehead, eyes, cheeks, lips, and jaw line all look pretty much the same to me. In fact, to my mind the 1987 photo is more similar to the 2002 photo, shot 15 years later, than to the 1984 photo shot just three years before while his face was still maturing — a similarity that completely contradicts the prevailing notion that Jackson radically changed the shape of his face after 1993.

Jackson’s mother confirms this, telling Oprah Winfrey in a November 2010 interview that Jackson had several surgeries on his nose, but not his entire face as widely reported and generally believed. Winfrey asks her, “As he continued to have other operations and changed the way he looked, did you feel like you could say something to him about that?” Mrs. Jackson responds by saying, “He had other operations on his nose, but any other thing, he didn’t, except his vitiligo.” Apparently, his mother just sees the natural progression of a maturing face as well, and I would consider her the ultimate expert on the subject.

So why was it so commonly accepted that Jackson had extensive plastic surgery? I think partly it’s because he defied accepted notions of race and identity by changing the color of his skin and the shape of his nose, so both the media and the public became obsessed with his face. The tabloids, especially, were constantly photographing and analyzing his face, searching for additional changes. He also had a very angular jaw line and prominent cheekbones that could look quite different depending on camera angle, lighting, and the expression on his face, providing the tabloids with plenty of material for speculation.

However, the occasional odd photograph by itself could not have caused the media hysteria that came to surround Jackson’s face. There was more going on than that, and the explanation lies in the nature of perception itself, and how our beliefs shape our perceptions: we see what we expect to see. Once the media and the public became convinced that Jackson had had numerous plastic surgeries — that he was, in effect, addicted to plastic surgery — they began to interpret the photographic evidence in ways that supported their preconceived ideas.

For example, here is a series of six images that emphasize Jackson’s prominent cheekbones and square jaw line:

And here’s another series of six images taken at an angle that makes his face appear thinner, his cheeks less angular, and his jaw line longer and narrower:

These six images look very different from the first set of six, yet they cover overlapping periods of time. If organized chronologically, they would be interspersed, like this:

The obvious conclusion to be drawn from this compilation of all 12 photos is that the apparent lines and shape of Jackson’s face varied a lot depending on factors such as the direction he was facing, his expression, his weight, and the type and direction of lighting.

However, that was not the explanation that was presented in the tabloids, and it was not what the public came to accept as true. The dominate narrative in the tabloids, and eventually in the mainstream media and the public mind as well, was that Michael Jackson was born with a cute pointy chin, rounded chipmunk cheeks, and a narrow jaw line, and then completely changed his face through obsessive plastic surgery, making his chin wider and more masculine and his cheekbones sharper and more prominent. And because that’s what our minds came to believe, that is what our eyes began to see. This progression as we imagined it looks something like this:

In effect, we highlighted and prioritized the images that fit the narrative we believed, and mentally edited out the ones that didn’t. And each time we saw a new photo, we evaluated it in terms of the pre-existing story line. If it fit the narrative and somehow suggested additional alterations to make his face more masculine, it was accepted as yet more proof of plastic surgery and was added to the “changing faces” photo series that sprang up like mushrooms all over the web. If it didn’t, it was largely ignored.

Just for fun, we could actually create a series of photos that “proves” just the opposite: that Jackson was born with a square jaw and prominent cheekbones and somehow had them shaved down over the years to appear more feminine, like this:

This narrative is just as plausible given the same photographic evidence, yet it was never once presented in the media. Instead, the dominant story line spread from the tabloids to the mainstream media without serious question or analysis, and by the time his obituaries were written it was generally accepted as fact.

Based on a review of the full photographic record, neither of these narratives is true. It appears that, except for changing the shape of his nose, Jackson had very little plastic surgery — just as he said throughout his adult life and his mother confirmed after his death. However, his claim that he had not radically changed his face through plastic surgery was generally treated by the press and the public as at best delusional and at worst an outright lie.

“I’ll be Grotesque before Your Eyes”

But how did the narrative that Jackson was obsessively altering his face through plastic surgery get to be so dominant? I think partly it’s because the tabloids and to some extent the mainstream media tend toward the sensational, and this story was certainly sensational: it fit their natural inclinations. But I also think Jackson himself helped perpetuate that narrative, as he basically said he would in “Is It Scary.”

For example, a bizarre story began circulating in 1995 that the tip of Jackson’s nose had fallen off during a dance rehearsal for his Scream video. Here’s a description from Rolling Stone magazine:

Jackson was practicing dance moves when his hand brushed his heavily altered nose. The tip of it—actually a prosthetic—flew across the room, and Jackson began screaming hysterically. Crew members ran after it. “There was a hole, man, a little hole, right where the tip of the nose should be, a perfectly circular opening,” says a source who was in the room that day.

This story strikes me as deeply suspect. I can just picture the scene: Jackson “screaming hysterically,” crew members scrambling after his “nose” in panic, others standing by watching in horror. It sounds like total lunacy, and perfectly in keeping with Jackson’s slapstick sense of humor. (He loved the Three Stooges, as well as Charlie Chaplin.) He was also an avid and accomplished prankster and very skilled with disguises. He would love to pull off a spectacular prank like this. As he told Rabbi Shmuley Boteach, “Are you kidding? That’s my most favorite thing in the whole world, to prank people.” Even more importantly, he had just told us the year before that he would “be grotesque before your eyes.” He seems to be predicting precisely this type of incident. So is it possible Jackson intentionally set up this rather “grotesque” scene to make it look like the tip of his nose had fallen off? I, for one, am very suspicious.

Jackson provides an intriguing hint that things aren’t quite what they seem in Ghosts, filmed the following year. At one point he transforms into a monster who seems to be missing the end of his nose, but he’s not. It’s there and visible the entire time; we just don’t interpret it that way. Jackson reveals how this clever but relatively simple illusion works by showing the makeup process as the credits are running. Here’s a screen capture:

We see that while the base of his nose is covered with layers of prosthetics, the tip of his nose is not. A ridge is created where the prosthetics end to suggest that the monster’s nose has rotted off, but his nose is actually there and visible. It’s just out of scale with the surrounding prosthetics so appears to be missing, or just the core of what should be there.

It’s an unusual illusion, and an interesting choice for depicting this character’s face considering the commonly held perceptions about Jackson’s nose. It’s even more interesting that Jackson chose to take us behind the scenes and show us precisely how it was created. Did he use a similar technique to pull off a “grotesque” prank during that dance rehearsal for the Scream video the year before? Is he giving us a clue about what really happened, and how he did it?

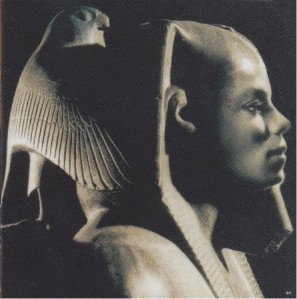

Jackson provides another clue in the liner notes to his HIStory album, which features “Scream” as the lead-off song. In a strangely beautiful image, Jackson appears as a sphinx — interestingly, a sphinx who has yet to lose his/her nose:

Through clues such as these, Jackson suggests he had far greater control over his “grotesque” public image than we realized — that the plastic surgery scandal, in particular, was an illusion perpetuated by Jackson himself.

The important question is why he did it. As Jackson tells us rather explicitly in “Is It Scary,” he intentionally became “grotesque before your eyes” as a response to public perceptions that he was a child molester, a “stranger in the night.” It was an artistic response that served several different functions, some of which are rather complicated, but one function was to show the press and the public just how wrong they were, how wrong their perceptions were, when they accused him of molesting a child. During the time when “Is It Scary” was written, Jackson was undergoing an “Armageddon of the brain” as he calls it in Stranger in Moscow. He was being judged by the media and the public, and increasingly the verdict was that he was a child molester, which was intolerable to him. It made a lie of him, his work, his entire life. But nothing he said or did made any difference.

Once the media and the public began to think Jackson was a pedophile, they began to focus on the evidence that supported that conclusion and largely ignored the evidence supporting his innocence. So while the commentators covering the 1993 scandal generally conceded there wasn’t sufficient evidence to find Jackson guilty, they endlessly repeated the circumstantial evidence against him, much of it hearsay and innuendo, and largely ignored the evidence that should have cleared him, or at least raised serious questions about the case against him. For example, almost no one acknowledged that the boy’s allegations were first made in a dentist’s office either while he was sedated or immediately after sedation — and either way, who knows what his father may have said to him while he was sedated, and what effect that may have had on the boy’s memories. Yet this is an undisputed and crucially important fact in this case since it casts significant doubt on the boy’s testimony, and his testimony is the only real evidence against Jackson. Everything else is circumstantial.

However, media coverage of the scandal, and the public reaction that followed, weren’t driven by a careful review of the evidence. Instead, Jackson was being tried and convicted in the tabloids and entertainment news media, especially, and in the minds of the public, based on raw emotion verging on hysteria, a strong bias toward sensationalism, “expert witnesses” with very little knowledge of this particular case, “informants” willing to exaggerate or even lie for profit, and the resulting misinformation and misperceptions. So Jackson embarked on an experiment to show just how wrong public perception could be. It was, in effect, an extreme act of performance art, but as he told Kobe Bryant, “it’s OK to be that driven; it’s OK to be obsessed with what you want to do.” In this case, “it’s OK” to push the definition of art to such an extreme to prove something so crucially important.

However, Jackson could have chosen a different illusion to prove his point. He didn’t have to become “grotesque before your eyes.” He chose that particular illusion for a reason.

In many ways, Jackson’s most enduring project was challenging and altering our responses to him himself as a cultural icon, as a black American man, and simply as a fellow human being. Throughout his career, he struggled with a public that sometimes idolized him and sometimes ridiculed him, but either way seemed perversely unwilling to see him as a person.

As he sings in “Breaking News” about the persistent rumors that his marriage to Lisa Marie Presley was a sham, “Why is it strange that I would fall in love? / Who is this boogeyman you’re thinking of?” In “Monster,” he parodies the media’s exaggerated depictions of him (“He’s a monster / He’s an animal”) but then flips that perspective, suggesting the media are the real monsters (“Why you haunting me? / Why you stalking me?”) and concludes with a warning that these media excesses hurt us as well as him (“He’s dragging you down like a monster / He’s keeping you down like a monster”). Wrestling with our inability to see him as a thinking, feeling human being became a career-long focus of Jackson’s art. And throughout his career, we see him responding to this problem in a very interesting way: by capturing the emotions the public is projecting onto him and reflecting them back at us, while fundamentally reframing and altering our response.

Jackson first appeared on the world stage as an extremely talented black boy growing up in a deeply racist country. And if the crowds thronging to see him are treating him with a fearful fascination like some sort of exotic pet — “like an animal in a cage,” as he told his mother — then he gives us an exotic pet: a rat, a boa constrictor, a tiger cub, a chimpanzee. But then he encourages us to sympathize with these animals. In “Ben,” his first chart-topping hit as a solo artist, released in 1972, he takes us inside the mind of a rat who is himself the victim of mindless prejudice, singing, “most people would turn you away” and “You feel you’re not wanted anywhere.” And in interview after interview, Jackson encouraged reporters to interact with his boa constrictor or his chimpanzee and see them in a less fearful way.

By 1983 Jackson had matured into a very sexy young man, and throughout our nation’s history, the image of the sexual black man has been seen as extremely threatening — so threatening that black men in the not-so-distant past were lynched because of it. Cultural taboos demanded the races be kept distinct without blurring the boundaries between them, which is why interracial relationships aroused such deep hostility for so long, and it’s important to remember that anti-miscegenation laws weren’t ruled unconstitutional until 1967. Some of the brightest and most confident young black men were tortured and killed out of fear that white women might see them as desirable. (Though that wasn’t what was said, of course — it was said they weren’t deferential enough to white women — but the message is the same either way: black men should not associate with white women.)

Now, not so many years later, a lot of young white women were seeing Michael Jackson as very desirable. He was a teen idol, our first black teen idol. This was uncharted territory, and more than a little threatening. Jackie Robinson integrated baseball, but Michael Jackson integrated sex, and that’s the deepest, darkest, most sacred taboo of all.

Jackson’s response was brilliant: he gave us Thriller. In other words, if white America has been culturally conditioned to see a sexy young black man as monstrous somehow — as threatening or alien or anything less than fully human — then he gives us a monster: a werewolf, a zombie. So again, Jackson captures our conflicted emotions about him and reflects them back at us. But throughout Thriller he shifts back and forth, back and forth, familiar to alien and back again. Jackson transforms seven times over the course of Thriller: sweet boy, werewolf, sweet boy, zombie, sweet boy, zombie again, sweet boy, some emerging unknown creature. Each time he shifts into a monster, we — as a culture, but white teenaged girls, especially — are able to express some of the conflicted feelings we’ve been repressing about him, about seeing a young black man as sexually desirable and sexually taboo, as physically attractive and physically threatening, as exotic and fascinating and kind of scary. And each time he shifts back, we’re reassured that he’s still that same sweet-faced Michael Jackson we’ve loved since he was a boy.

A decade after Thriller, in 1993, Jackson was accused of molesting a young boy. And if we’ve heard the accusations of pedophilia and feel a secret shudder at the sight of him, then he makes that loathing materialize on his face. That’s why we as a people were so mesmerized by the image of his “ravaged” face, and why it resonates within us so deeply. Like “Ben” and Thriller before it, it precisely aligns with submerged emotions we’re already feeling about him, gives us the symbolic landscape we need to fully express those emotions, and then reflects them back at us, making them visible.

But it’s just an illusion. He hasn’t really changed. It’s only our perceptions and interpretations of him and what we project onto him that’s changed, not him. He’s still the same as he was before the allegations — as he sings in Stranger in Moscow, “Lord, I’m the same” — and he’s still beautiful, if we have the eyes to see it. (It’s interesting that this illusion seems to have replicated how specific individuals felt about him. Those of us who thought he was innocent tended to see his face as vaguely different somehow, but not disfigured. Those who thought he was guilty tended to see his face as “ravaged.” And a few excitable individuals saw his face as truly hideous, apparently.) So as with “Ben” and Thriller, he provides us with the symbolic landscape we need to fully express all our conflicted emotions about him, and then forces us to confront those feelings and begin to work through them.

Jackson repeatedly challenges our deepest, most repressed emotions about him, and he does so by speaking to us directly in the language of the subconscious. If white America in the 1980s were somehow one of Freud’s patients, and we told him that the cute little black boy next door had grown into a very attractive young man and we’d been having dreams that he became a werewolf at night, Freud would have known how to interpret that immediately. And if we told Freud 10 years later that the young man next door had been accused of molesting a young boy, and we’d been having dreams that he was so horrified by the accusations he cut off his nose, Freud would have known how to interpret that as well.

While the idea of Jackson symbolically cutting off his nose may not make much sense at the conscious level, it makes perfect sense at the subconscious level — maybe that’s why so many people were ready to believe such an unbelievable story — and we respond in emotionally and psychologically complex ways even if we don’t consciously understand it. In fact, stories like Jackson befriending a rat or becoming a werewolf or cutting off his nose may work best when we don’t understand them — when we simply give in to them and fully experience them, and don’t analyze or resist them or try to control our own responses.

I think about Jackson’s “eccentric oddities,” as he calls them in “Is It Scary,” and how we recoiled from them so violently, and I wonder what that tells us, not about him, but about us. Just as our reactions to the changing color of his skin reveal our submerged feelings about race, maybe our reactions to his “eccentric oddities” reveal how we tend to respond to difference more generally. And maybe, as Jackson shows us in Ghosts, art has the power to change the way we perceive and respond to the differences that divide us.

“So Let the Performance Start”

The more I’ve studied Jackson and his work, the more convinced I am that he was a man of tremendous courage and deep psychological insight, fiercely committed to social change, wryly funny even during the most difficult times, and an artist to the very core of his being. He saw everything in terms of art and the transformative power of art. We have no unmediated access to the world — we can only access the world through our senses and perceptions—and art has the ability to challenge and change those perceptions. That is a tremendous power, and Jackson understood that better than any other artist of his time.

For example, as Jackson’s vitiligo symptoms became progressively worse, he could have responded by covering the white patches with dark makeup the rest of his life, as his makeup artist, Karen Faye, says he did the first few years of the disease. Or he could have fully disclosed everything, worn minimal makeup, and become a spokesman for vitiligo awareness and treatment. Instead, he developed an artistic response that challenges our most fundamental beliefs about race and identity, and has changed us and our culture in ways we have not yet begun to measure.

In the same way, Jackson could have responded to the public perception that he was a child molester by trying to ignore it or rise above it somehow, although it’s hard to see how he could ignore an issue so at odds with his central beliefs. Or he could have retired from public view entirely and enjoyed a comfortable private life with his new family, something he’d never had before. Instead, he developed an artistic response that shakes the foundations of perception itself, and challenges some of our most basic assumptions about how we see, interpret, and make sense of the world.

That is the work of a powerful artist.

wonderful work…….very well explained….!!

Michael actually had very few plastic surgeries they emphasized on it because he’s Michael Jackson as you mentioned the most famous man in the world and they were trying to tear up his reputation.

This is my first time i visit here. I found so many entertaining stuff in your blog, especially its discussion. From the tons of comments on your articles, I guess I am not the only one having all the enjoyment here! Keep up the good work.

I was thinking of actually doing the same thing with the pictures! I hadn’t actually seen it lined up like that, but now that I have I see it even more. He had three, four surgeries at the very most. And since he was on a strict diet, he lost a lot of weight as he matured, which I know can change how your face looks dramatically. Did my face when I was a tween look the same as it did when I was a toddler? Nope. Even a few years can make a difference, and my face looks different now than it did even then, and I’m fourteen. Will my face look the same as it does now when I’m an adult? Probably not. Your face changes a lot when you mature, and losing weight can make your face change too. I had the flu for a week, and my face actually changed during that week. It has since gone back.

Hi Emily. You’re right, our faces do change naturally over time, and photos of our faces can look really different at times because of camera angle, lighting, our expression, and other factors. I know I’ve seen a couple of photos where I hardly recognize myself. They caught me at a weird angle or something, and they just don’t look like me – at least I hope I don’t look like that!

The blog Vindicating Michael has some wonderful composite photos and photo series, such as this composite image from 2007 (on the left) and 1988 (on the right):

Looking at this composite image, I see no sign of plastic surgery. This is consistent with what I’ve found elsewhere. After reviewing hundreds of images, I see no structural changes to his face after 1988. And the only changes I see before 1988 are to his nose and the chin cleft, just as he said in Moonwalk.

To see the entire article at Vindicating Michael, as well as more images – including the two images they used to create this composite – click here.

This is the best article I read about the King Michael Jackson. Thank you so much it’s the best blog fans must read.

Reading this gave me goosebumps. Amazing, incredible and informative insight into the Genius that is Michael. Thank you so very much.

God Bless you

Genius work.

What a great article and thoughtful and intelligent analysis of this subliminal side of Michael Jackson. So many didn’t “get” him and judged him by their own inferior standards (with an awful lot of help from toxic media reporting).

In various scenes in the “This Is It ” documentary, where he is virtually make-up free, it is easy to see his ” natural” and older face. In my opinion, at whatever stage in his life, he always looked very attractive. I liked the older version, and it does seem as though Michael often used his face as a canvas when in the public arena. The fact that he aged like everyone else does, seems to have been omitted in the unnatural obsession with his “altered” appearance.( Yet another of his “crimes”).

As far as the “child molestation”, we know that the general public never had a chance of hearing the true facts, which in most instances, were maliciously witheld in favour of sensationalism, and so they believed without question what they were being force-fed.

So gleefully did rational, intelligent people soak this up, that I have never heard anyone suggest that the children involved should have been protected from their own parents, not Michael.

When I indicate that I admired Michael as a man, not just as an entertainer, people act surprised, and I sometimes get the “look”. I might respond by raising my eyes to the sky and shaking my head, but sometimes I have suggested that they can’t have a very high opinion of me, and I feel insulted, if they believe I admire a “child molesting freak.” This will often provoke an embarrassed mumbled “well of course we’ll never know ” or it leaves them totally “Speechless”.

Why is it that all too frequently, all common sense seems to disappear when Michael’s name is mentioned ? (I should add I only do this with people I know well, and who know I hold strong views on lots of subjects, and often pull my leg unmercifully. The last thing I would do is alienate them even more, and hopefully they might start to think differently).

Michael always indicated that he knew that huge responsibility came with his talent. At what point, I wonder, did he realise he would inevitably be vulnerable to the baser instincts of human kind, and to what degree he would be made to suffer?

Many of us know him for his message of love and compassion, his dignity, humanity, and his unfaltering loyalty to the truth. The truth can never be changed, but a lie once told has to be maintained by more lies, until the lies become in conflict with themselves, and the liars become more irrational.

A life cut short, that impacted on so many, but a life well-lived and an example to others, I still believe the majority of people, even if somewhat indifferent to him, know Michael for what he really was, and always will be.

Thank you for posting this thought-provoking article.

The man had vitiligo plain and simple so what’s so wonderful about misguided psychobabble that totally ignores the significance of that fact and seeks to find some other causes? I don’t understand how anyone is still confused about this and needing to contemplate his “changes.” MJ knew about another performer, Arthur Wright, who had Universal Vitiligo and he simply did the same thing Arthur had done before him. I think it’s interesting how much stuff people make up when the answers are so very simple. Now that is worth writing about. Here – the article about Wright from 1978. http://books.google.com/books?id=EdQDAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA165&lpg=PA165&dq=ebony+the+man+who+turned+white&source=bl&ots=dVHI9hwkju&sig=fdRNeWCLLguqXdyKAq0Fspu78TE&hl=en&sa=X&ei=FAoMT47QL8y3twexrcTrBQ&ved=0CB4Q6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=ebony%20the%20man%20who%20turned%20white&f=false

Wow! I NEVER heard/read anything about that artist. Thank you so much for that article!! “Now that is worth writing about.” I absolutely agree with you but obviously it was/is not that simple I´m afraid. Nothing is “wonderful” about that ignorance but it does happen again and again and it´s dangerous, so it´s very important to deal with it, to understand how things like these come to happen and maybe how to avoid all that in the future.

Michael was diagnosed with lupus in 83–also an autoimmune disease like vitiligo. This is what Dr. Richard Strick, a court appointed dermatologist, said in 93 after examining Michael’s records: “Lupus is also an autoimmune disease and he also had skin involvement which had destroyed part of the skin of his nose and his nasal surgeries and all were really reconstructive, to try and look normal.” Another quote from Dr. Strick: “The first one [reconstructive surgery] was to try and reconstruct from some scar tissue and obstruction that had happened with the skin there. It didn’t work out very well and all subsequent attempts were to make it right.” “I think he was trying to look like a normal guy as best he could.” This is all b/c lupus causes skin lesions. Here is a quote from Dr. Brooke Seckel on lupus: “Lupus can cause large areas of skin on the face or tummy to actually die after plastic surgery and result in terrible scars.” So I conclude that Michael had the 2 surgeries he referred to, but that due to his lupus, lesions formed at the site of the surgery and then he undertook, as Dr. Strick said, reconstruction surgeries to try and handle what was happening to the skin around the location of the surgery–maybe the lesions or the dying of the skin, as Dr. Seckel notes. It must have been terrible to face all these physical problems–vitiligo, lupus, back pain, the burn on his scalp–and all the psychological issues from his childhood and the allegations–and yet have the media poking, prying, misunderstanding, fault-finding everything.

Thanks for your article–you are right, he did look the same in terms of his basic facial structure. Do you think some of the focus on his ‘addiction’ to plastic surgery was b/c as a man it was not accepted to openly have any plastic surgery at all?

This whole media attack on Michael reminds me of the Salem Witch trials–once accused, there as no possible way to prove you were not a witch. It seems the same happened to Michael–accused and no matter what he or anyone else said in his defense, the charges stayed in people’s minds– Tom Sneddon’s as well as the public’s.

I also read a recent article about the failures of the US Justice System. The writer says that in USA, prosecutors do not comply with the defendants constitutional rights, that there is no sanction on them for violating these rights, and that Grand Juries are a rubber stamp for the prosecution. He says the presumption of innocence is an ‘heirloom’ of the past and that what we have is an “evil and generally defective system that thrives on complacency.” He also says that prosecutors in USA have a 90% success rate in prosecutions, and that USA has 50% of the world’s lawyers. The author is Conrad Black and the article was in the Huff Post. In a case of prosecutorial misconduct the person (MIchael) has little recourse as prosecutors have virtual immunity from civil recourse for their actions and the only sanction is ‘professional discipline.’ (LOL)

Thanks for all you are doing here in this blog!

I burst into tears when I read this. It never occured to me that Michael was taunting the stereotypes of gender and race. I mean, I knew he didnt care what the press and media thought of him; that he was comfortable in his skin, in spite of some people saying he wasnt. I knew he challenged the boundaries of society, which I always admired him for, but how much of a sacrifice he made, was not apparent to me until I read this. It makes me honor him even more, if that is possible. This man had much to teach this world,and slowly people are beginning to see the humanity and genius of Michael Jackson. Thanks to the author of this. Incredible insight. A great tribute and great understanding of the person MJ!

michael is beautiful he always has been inside and out

if God came down to earth now … he’s face …. MICHAEL SO MUCH IS THE PURITY OF HER FACE

Hi, Willa, great article.

Can you tell em where you got this “Evan’s account”, please?

Hi Daniela. Believe it or not, the quotations of Evan’s chronology – the one he gave to police – are from Diane Dimond’s book, Be Careful Who You Love (page 60 – I believe this link will take you there). So these are Evan Chandler’s own words.

It really does show how fully belief shapes perception. Dimond went into this case believing that Michael Jackson was guilty, so she sees Chandler’s chronology as proof that he was a good father encouraging his son to unburden himself of a painful truth. However, to me the chronology proves something very different: that he lied and coerced and manipulated his son to give him the answer he wanted.

Oh, Thank you, Willa.

And this is the best about MJ enemies. They can’t see the truth (unfortunately), but they give it to us while try to convince us Mie was guilty. It’s the same about Ray Chandler’s book. He gave us a lot of very important information against themselves.

Oh, change the subject, Willa, in Stranger in Moscow, MJ says “Lord, I must say”, not?

Well, this is what a hear. Lol.

There are no letters to this song in the insert.

I always heard it as “Lord have mercy”

Hi, Willa, Thanks for that link to DD’s book. The claim that Jordan was not coached is contradicted by Geraldine Hughes in her book Redemption. She was the legal secretary for Evan’s lawyer and she saw Jordan alone with the lawyer, Barry Rothman, right before his meeting with the first psychiatrist Dr. Mathis Abrams, who was the one who reported the suspected molestation to child services, who then reported it to the police. Why was Jordan alone in Rothman’s office without his father if not to rehearse what he was going to say to Abrams?

The claim that Jordan was able to suppy dates and times is also not true. In his interview with Dr. Gardener he often can’t remember what month, let alone a date. And he can’t remember how many times the alleged molestations happened. He can’t remember whether it was before the summer of 93 or after the summer. The memory lapses are unbelievable, and also happened with the Arvizo boy Gavin, who said on the stand, ‘to this day I can’t remember when it happened’!! This is why Sneddon changed the dates between the arrest warrant and the charges. These are 13 year old boys who claim they had had no previous sexual experience, barely ever had an ejaculation before, and yet they can’t remember when they had sex with–hello–Michael Jackson??? In speaking with Gardener, Jordan claimed he had had one ‘wet something’ before.

You make an excellent points about the coercion Evan practiced, which DD glosses over. Also the ‘promises’ made in that conversation are remarkable for their betrayals.

Do you think there is a connection between the nose and the penis? Was the missing nose idea part of the effort to metaphorically castrate Michael? There are some people who actually do believe he was castrated, either literally or via hormones by his father in order to keep the high notes. This idea is of course nonsense and debunked by the autopsy, but, I mean, could the image of a nose falling off be related to a penis falling off as a subliminal image?

Hi Aldebaranredstar. You know, in general I tend to be kind of wary of overly Freudian readings like equating a nose with a metaphorical penis. (As Freud famously never said, but should have, sometimes a cigar is just a cigar.) But I really do think there’s something to it in Michael Jackson’s case, both in the public obsession with his nose and in his response to that obsession.

It’s really interesting in this context to look at Mikhail Bakhtin’s Rabelais and His World, where he talks about how grotesque representations of the human body, especially the human face, were a way for folk culture of the Middle Ages, especially, to defy and resist authoritarian power structures – something I see as very applicable to Michael Jackson. And according to Bakhtin, “the grotesque image of the nose … always symbolizes the phallus.”

There is a thing I desagree, willa. It’s about waht you said about vitiligo. “….he could have responded by covering the white patches with dark makeup the rest of his life…”

I don’t think it would be so easy, if we consider his vitiligo reached 85% of his body. I think he tried cover the blanched blanched spost while he could, but, in a point of the time, he could figth against the fact he was turning white , as Karen said, “…we need to opt for the white model”. I mean, he couldn’t hide his condition for the rest of his life. Beacuse he had a private life, he wasn’t just a artist, and he couldn’t hide his condition from himself. I mean, what would be the sense the world thins and see him as a a man with dark skin when he wasn’t? In his private life he couldn’t hide it. Imagine if he could hide it from a girlfriend, for example. No.

In my opinion, he had not a choice. And to me it is very disturbing. Just think about it – if you believe in God, fate, whatever – WHY the black man who came to be the biggest entertainer of the world could not avoid becoming a black to white? Why him? It seems so unfair to me. But, in the same time, I think there’s a reaseon for thatm, as God, the Universe, whatever, were trying to tell us something.

Hey Daniella, I totally agree here. I also remember Karen Faye saying something like with the kind of performer Michael was, with a lot of dancing and perspiration, it really wasn’t possible to cover it up with dark make up – it would melt on stage. So, once it passed a certain stage he didn’t have a choice of covering it up. But he could choose how to respond to it. He never spoke about it, but he must have spent a lot of time agonizing about it and asking the why question that you are asking.

I think that is the irony of fate. It is especially ironic that it happened not only to the most famous black artist, but the most famous artist period. But it also speak volumes about Michael’s strenght! How many fragile child stars would hide and give in to justified self pity if it happened to them?

I think we ourselves are responsible for whatever message we take from the universe and pass along. I think Michael the man might have hated his appearance, but Michael the artist saw the opportunity to use himself as a canvas, like Willa said. Isn’t it funny for a guy who always said he thought he was ugly, at the same time to do tons of professional photoshoots and videos. He didn’t exactly hide his face.

Hi, Danielle, I agree as the vitiligo progressed, the option to use dark makeup to cover the white spots was no longer viable. I believe it was David Nordahl who said that these white spots were not white like a caucasian person’s skin–they were white like a refrigerator. In other words, devoid of all pigment, like an albino. I think this is not only why he used the white make up on the remaining dark spots, as opposed to trying to cover white areas with dark make-up, but also why he went for tattoos to give color to his face–tattoed eybrows and lips and hairline. This way he did not not look so much like an albino. Dr. Strick said everything he did was to try and look like ‘a normal guy.’

have been reading M Poetica again (soooo looking forward to the update) and finding Willa’s ideas absolutely fascinating, and to me they make total sense. I also wondered why someone who thought he was ugly would spend so much time and effort being photographed and videoed for his own sake. I never really subscribed to that idea of Michael’s thinking about himself, though in Defending A King there is mention that his security team would have to uncover all the mirrors when they left a place??

i believe that, like Andy Worhol, Michael did see his body as being a work of art (Lisa speaking of him as having “resculptured himself”) as Willa says, but more than that i agree that he loved blurring boundaries and expanding defintions to become inclusive as he did with skin colour, gender, sexuality and nationality.

Only becoming a fan after his death, I am not familiar with Michael as a cute little black boy or teen idol, apart from pictures of him. For me, as seen in his later short films and live performances, he appears as a ‘white’ man, and so I think of him in that way, while being aware that he was proud of his black heritage and soul. He has very much become inclusive in that way to me, and i think of him not as handsome, which implies masculinity, but as beautiful which is much more inclusive of his gender and sexuality – he is absolutely hot male sexuality in those gold pants in History, and lovely soft feminiity for instance in some of the shots of his face in the short film You Are Not Alone when on the stage alone.

Yes Willa, he was, and is, brilliant is all aspects of that word as well.

Hi Caro. Thank you so much for the kind words! That really means a lot to me. The second edition of M Poetica is now available (it went up this morning) but if you wait until Thursday, it will be free. In fact, it will be free from Jan. 10 – 14. I’d really like to make it available to any Michael Jackson fan who wants to read it, so feel free to spread the word to other fans. And you don’t need a Kindle to read it.

That’s great Willa – I just really wish that you could somehow get a publisher and be fully recognised and rewarded for such a wonderful book. I presume it is on Amazon.com again? and will certainly tell my MJ fan friends about it, those with and without Kindle. Keep up the good work.

Wow, Willa, you are very generous to offer your book for free. I got the firts edittion and I’m anxious for it’s reissue. And I just sorry nothing are launched in portuguese. We, Brazilian fans, are despised.

Genle, I todl black artist not because I think he was the biggest black artist, no doubts, he was the biggest artist. Perios, as you said.

What I mean is, he was the hero for black people, you know, he was the black poor littlte boy who became a king. He was a very beatiful and fill of talent Black King.

He surpassed all barriers, and he was loved around the world. A black man king not in a cauntry, but in the whole world, it means a lot to me.

So, was very unfair he has turned white due to illness. As he was being punished. But punished for what? Or maybe it all happened for a purpose, I have not figured out yet

.

Michael suffered, truly suffered, from vitiligo. He did not will himself to have white skin as some sort of artistic statement. Vitiligo is very disfiguring to people with brown skin. The wonder is that Michael was able to manage a relatively smooth transition right before our eyes. But he wasn’t trying to transgress any racial boundaries – vitiligo made his skin white, not his racial identity.

You sneak in “sexuality” as a category that Michael supposedly transgressed. How? He never presented himself as anything other than an ordinary heterosexual man.

Hi VC. I agree that “Michael suffered, truly suffered, from vitiligo.” In fact, Joie and I talked about this in one of our very first posts, not long after we started this blog. Maybe this will help clarify where we’re coming from.

Bravo. Bravo! What a wonderful, insightful post.

It seems to me that Michael’s artistic response, in serving as a “collective mirror,” was innate, always there, even as early as the song “Ben” which you pointed out. Although he didn’t write the song, as a young boy, he delivered it with such emotion, it was so believable. If you were touched by that song, as I was back then (being the same age as Michael) you felt that Michael was felting your own feelings.

Imagine yourself at 11 or 12 with all of the middle school angst, cliques forming, and being one of thise kids who was always chosen last for any spports game in P.E. Consider the lyrics of “Ben” from that perspective:

Ben, most people would turn you away

I don’t listen to a word they say

They don’t see you as I do

I wish they would try to

I’m sure they’d think again

If they had a friend like Ben

40 years later and I can type those lyrics from memory without Googling them.

(Also, those lyrics are remarkable foreshadowing – for I believe most of who appreciate his art feel exactly this way about him).

Here is Berry Gordy talking about Michael as child:

“… he was…beyond his years… when he did the song “Who’s Loving You,” the Smoky Robinson song, he sounded like he had been living that song for 50 years….He had a knowingness about him. At 9 years old, when I first started working with him, he seemed to me like he had been here before”.

Wow…

Willa this is me replying to my own post above, from yesterday. I just this minute was previewing your book on Google Books (I had not read it before) and I came upon page 209 where you wrote about Ben and said that you were an 11-year old completely obsessed with Ben, and then you quoted the exact same lyrics I had typed above.

Well I guess this proves the point you were making in your book. I had no idea at all – I hadn’t read your book – when I posted the comment above yesterday. It’s pretty spooky…I swear I was not quoting you; just speaking from my own experience.

I am off to Amazon to buy it this minute!

Hi GodsGlow. Actually, your description of listening to “Ben” as an 11-year-old makes me smile because it reminds me so much of my own experiences, and how much that song meant to me. Thanks for bringing back some good memories!

I was not a big fan of Michael Jackson. In the years since his death I have come to love this artist from his earliest years on. And being 65 years old some people in my life have no understanding of my emotional feelings about Michael Jackson. They think I’m 1 card short of a full deck His music, his performance art and all that he was I love deeply. So I am moved to write this blog (my first ever) to let my feelings out.

Michael Jackson we fell in love with so early in his life had to endure constant critical comments about his appearance. We must remember he was an artist to his core and he did what he wanted to do with his life as an artist.

My question is ‘would we have accepted him with his vitiligo in full view or turned our eyes away from him?’ Think about victims who go through transformations from accidents or disease.

We wanted Michael to look like the child we fell in love with and not the journalistic bull shit that was hoisted on us about his appearance.

Secondly I believe Michael knew if he was seen with full blown vitiligo we would turn away from him.

I’m not even sure what I would have done.

If this is the wrong forum for my blog I apologize. Again, my first, ever.

It’s strange how it’s perfectly okay for say a breast cancer survivor to get their scars made into art with tatoos, but not okay for michael jackson to endure his vitiligo affliction by turning that into art. I think his friendship with Dave Dave speaks volumes, besides the fact that we forget Michael was a burn victim as well as a victim of vitiligo and lupus, and i think how some people are affected by one small pimple. even if its tiny it seems to be the only thing you can think about. you imagine its bigger than it really is, that its all people see when they look at you. I think michael felt this way about his afflictions on some level. i think the face he felt he had sometimes might have been closer to the face of dave dave.

I just saw this today. I’ve often wondered what would have happened if Michael wore his vitiligo spots like a badge. http://thisisafrica.me/lifestyle/inspirational-chantelle-brown-young/

advanced apologies if i am being nosy(not a pun), buti am coming from a place were Vitiligo

is a common skin disorder, (even my neighbor has it), although it is a fact that jackson infact had vitilligo ,i simply cant understand the skin tone change in bad era, usually for vitilligo patients skin doesnt become middle tan , and then white any xplanation?( again sorry if this isnt about his work.)

Thanks for the pingback to Keely Meagan’s blog “Fooled by the Glitter.” I highly recommend it!

Mind blown! Amazing! I’ve only just started to get back into MJ after years of enjoying other music (I was a dangerous girl, so didn’t get into the hype, I was all about the Backstreet Boys lol). The more I read about him the more Jackson blows my mind. I’m sure 99% of the population just looks at him as a superficial pop star but they are all so wrong. I truly hope that MJ gets the kudos that he deserves.

Brillant!

This article made me think in ways that I hadn’t before. I will continue to read your work. Thank you.

Pingback: How to Recognize and Refute the Fallacies Used By Michael Jackson Haters, Part 2 of 5 « Vindicating Michael

Pingback: How to Recognize and Refute the Fallacies Used by Michael Jackson Haters, part 2 of 5 « Fan Blog for MJ

Pingback: Why I Love The Mature Face of Michael | AllForLoveBlog

Pingback: Why I Love The Mature Face Of Michael – Source: AllForLove Blog – By Raven (Reprinted By Permission Of The Author) | ALL THINGS MICHAEL! ♥

Pingback: Willa Stillwater – Rereading Michael Jackson – Michael Jackson Academic Studies

Pingback: Fooled by the Glitter: Michael Jackson and Social Change

Pingback: MJ Academic of the Week 12/12 – Willa Stillwater & Joie Collins – Writing Eliza

Pingback: Michael Jackson neu lesen | all4michael