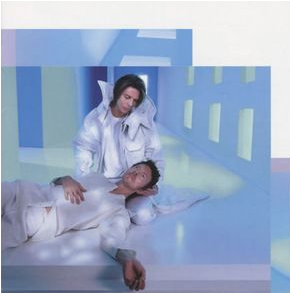

Make That Ch-Ch-Change: Michael Jackson and David Bowie

Lisha: In a previous post with Elizabeth Amisu and Karin Merx, we began discussing the late David Bowie as an important influence in Michael Jackson’s work. Specifically, we mentioned the theme of isolation and alienation in Bowie’s 1969 music video Space Oddity, and how strongly it echoes in Michael and Janet Jackson’s 1995 short film, Scream.

With the news of David Bowie’s recent passing, we wanted to take another look at some of the connections between him and Michael Jackson. Willa is off this week, but not to worry! She will be back soon. Elizabeth’s upcoming book, The Dangerous Philosophies of Michael Jackson: His Music, His Persona, and His Artistic Afterlife, features a fascinating comparison between Michael Jackson and David Bowie. So I’m really excited to welcome Eliza and Karin back to discuss this more!

Elizabeth: Hello again, Lisha. I’m so pleased to be back for a post on the late great Bowie. I was so sad to hear the news. But he has left a great legacy behind.

Lisha: He really has, and it’s wonderful to have you both here to talk about it. Thank you, Elizabeth and Karin.

Karin: Hello, Lisha, nice to be back for a Bowie post. All the great ones seem to go way too early.

Lisha: That does seem true, doesn’t it?

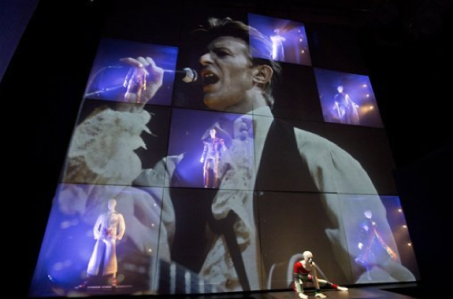

I was wondering if either of you happened to catch the David Bowie exhibit at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 2013. It was a fascinating collection of artifacts from David Bowie’s own archives simply titled: David Bowie Is. I understand the exhibit is touring internationally now. I have to say, it’s one of the most beautiful museum exhibits I have ever seen, featuring these magnificent multimedia displays of Bowie’s work:

As I was walking through the exhibit, I couldn’t help noticing a lot of Jackson/Bowie connections, although I hadn’t really considered it much before. Just curious if either of you had the same experience.

Elizabeth: Hey Lisha, I’m glad you brought this up. I spend a lot of time at the V & A for my research so I caught glimpses. I also perused the book, David Bowie Is, and it’s really something special… So many comparisons and connections between the two. What kept striking me is how Bowie’s influence and his uniqueness is really regarded by the British “establishment” while Jackson is often only begrudgingly tolerated. I thought, I understand exactly why the V & A would host this, but in the same breath, an exhibition on Jackson would be equally wonderful.

Lisha: You read my mind! David Bowie is taken up as a “serious” artist, worthy of a major exhibit at one of the world’s finest museums, while Michael Jackson still gets a fair amount of the wacko treatment and worse. I wonder how David Bowie was so successful in constructing his image as an important avant-garde artist?

Karin: I thought about that, Lisha, and I think it has to do with several factors, including cultural. First of all, when Bowie started his Ziggy Stardust in 1972, it was based on Glam Rock (glitter, high heel boots, etc. – typical British) and lots of teenagers felt drawn to it. It was a way they could express themselves and be accepted. But I don’t think that Bowie was as such tolerated in America. So there we already have a cultural difference.

Lisha: I do get the feeling that David Bowie’s impact in Britain was quite different than in America, although he enjoyed tremendous popularity in the US as well. What else might account for this?

Karin: Pop music, I think, is more a British invention than it was an American. And if you know that a lot of the popular music in America has its roots in black music and was taken over by white groups, then there is already a significant difference. Both, by the way, had their cultural revolution in the sixties and the beginning of the seventies – all a reflection from the second World War, although the US was fighting for equal rights for black people, and had their own war in Vietnam. There were a lot of artists in Europe that demonstrated against that war.

Lisha: You bring up a good point. There’s been a very productive musical dialogue between Britain and the US for some time, with musical innovations traveling back and forth. Of course this includes British Pop and American R&B, which were hugely influential for both artists.

But for some reason I don’t remember Bowie receiving such strong push back in the US, the way Michael Jackson did. Am I wrong about that?

Karin: Umm…wasn’t it Bowie who said he was bisexual in the US? Being controversial just because? That certainly did not fall into good soil …

Lisha: You’re right, that would certainly invite controversy! No doubt about it, especially in the 1970s. But as I reflect on David Bowie’s work, one of the things I admire is how effective he was at leading societal attitudes. He wasn’t so many steps ahead that you couldn’t read what he was doing and follow along. For example, there have been some wonderful stories recently about how effective he was at addressing social prejudice towards the LGBT community. I think it’s an important part of his legacy.

Elizabeth: You’re so right, Lisha. I watched an interview with him where he said that discussions about his sexual orientation really affected his ability to be as successful as he wanted to in the States.

Lisha: Interesting.

Elizabeth: Jackson also had a lot of rumours about his sexuality. I wonder why that often seems to be the first questionable subject when a maverick appears in the industry.

Lisha: That’s an extremely important question. Refusing to conform to social constructions of heteronormativity is often considered very problematic, and we’ve seen a number of popular musicians challenge this in a very productive way. But when rumors of sexuality combine with other factors, such as racial politics, things can really get ugly. Michael Jackson faced backlash that I don’t think any other artist has had to deal with.

For example, I don’t recall anyone challenging David Bowie about his one blue eye. No one called it weird, claimed he surgically altered his eye, or made comments about eye color and racial identity. It was just accepted he had an eye injury and that was that. His blue eye read as edgy and cool.

Elizabeth: That is SO TRUE! Bowie’s eyes were seen as obviously having a serious medical reason, another thing that made him unique and special and enigmatic. However, the dominant narrative about Jackson altering himself (starting in the 1980s) quickly became the go-to answer for everything about his physical changes. It is unfair in a lot of ways.

Lisha: Incredibly so.

Elizabeth: Also, it seems that eye colour is not nearly as contentious as skin colour. Due to the legacy of racial stereotyping and eugenics, ethnicity has so much added cultural value. Some of which is so deeply ingrained that we don’t even know where exactly it stems from.

Lisha: I agree. And society could choose to categorize people by eye color, but for whatever reason we don’t, except perhaps to praise the beauty of blue eyes. Of course that raises a very troubling question: why should one eye color be valued more than another? It’s a problematic notion that no doubt carries a lot of historical baggage.

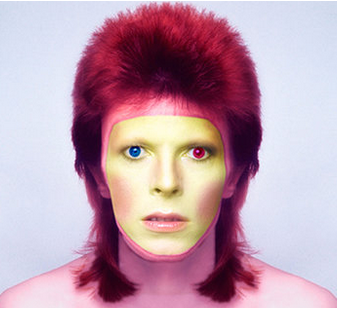

Here’s a photo of Bowie playing up the difference in his eyes:

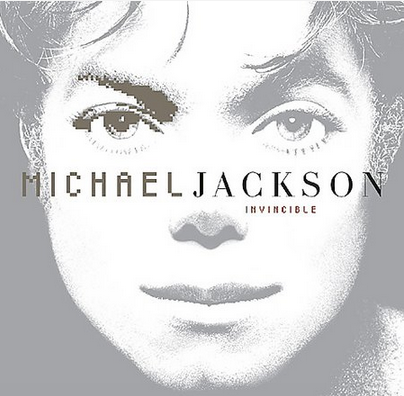

I find it fascinating that Michael Jackson also experimented with different eye colors for the cover of the Invincible album:

Here’s another photo by Arno Bani that was considered for the cover of Invincible:

Elizabeth: Yes, Lisha. I’m so glad you introduced Invincible into this discussion because it’s so often overlooked. Invincible is possibly Jackson’s most avant-garde album. It wasn’t really designed to be a people pleaser so much as an artistic expression of Jackson’s own making. The cover and the illumination of the right eye (the viewer’s left) is particularly interesting. Again, it is unexplained but I always draw attention to the pixelation of this eye indicates Jackson is becoming digital, on the cusp of a digital age, and that digital sound is really evident in songs like 2000 Watts. Also, there is the adage, ‘the eyes are the window to the soul’. Hence why on the cover of Dangerous we look into Jackson’s eyes and are confronted with an explosion of all these images which proliferate around them.

Lisha: The single pixelated eye found on back of the album reinforces your points quite well. That’s a wonderful connection you make between the digital cover art and digital sound of the recording! I agree it’s an album that deserves much more attention.

Thinking about all this just made me flash on another Bowie move, which is the bright red Ziggy Stardust hairstyle that’s been called “A Radical Red Revolution.” Suzi Ronson was the hairstylist behind the look, and she said that Bowie wanted to do something different from the typical long hair in rock music. So she cut his hair short and dyed it bright red to create a look that was antithetical to rock at that time.

Last summer I was doing some research and was surprised to learn that red hair is commonly stigmatized, especially in Britain, where it is associated with Irish and Scottish descent. It got me to thinking about how David Bowie’s red hair reads as super glam rock cool and really busts through this social prejudice, whether it intends to or not.

Red hair is also part of a familiar comedy routine – the classic clown character – which has been interpreted as a parody based on prejudice towards the Irish and Scottish. According to The Racial Slur Database:

Not used so much as a racial slur, however, the classic clown is based on a stereotyped image of Irish people: bushy red hair, a large red nose (from excessive drinking), and colorful clothes often with plaids, and often with a great many patches to represent that the Irish were poor and could not buy themselves new clothes. With excessive plaid is a Scottish variation.

Getting back to Michael Jackson, there is considerable overlap in the history of clowning and blackface minstrelsy, both of which feature comical characters with painted faces and bushy wigs. Willa and I talked with Harriet Manning a while back about her work on blackface minstrelsy, and she very convincingly showed how Michael Jackson engaged with these demeaning stereotypes while effectively turning them inside out.

So I think we can draw a connection between Michael Jackson and David Bowie as artists who have engaged with deeply ingrained stereotypes and their historical representation. They’ve done important cultural work by pushing back against social prejudices that have been perpetuated through the entertainment industry. Most of this work flies under the radar of public awareness. As you said, Elizabeth, these stereotypes have become so deeply ingrained, we often have no idea where they came from.

In regard to the response it generated, what are other explanations for why Michael Jackson and David Bowie were treated so differently in the press?

Karin: Bowie did not disappear from the public, unlike Michael Jackson after his massive Thriller success. That gave the press all the space to create their own stories. And Bowie developed all his personas, created with 27 studio albums, whereas Michael’s personas were, probably because of his absence most of the time, created by the press (the monster) and fans (the angel) etc. Furthermore, Michael could have created tons of albums, but only made about 6. I think that if you can follow an artist and his development, and here Bowie and his personas, the combination, theatre/pop-music, it is like following the development of an artist, who is then taken seriously and accepted as an artist.

Lisha: I agree that the amount of effort, time and money that went into Michael Jackson’s mature work meant there were not going to be a lot of albums to promote. And musically, I think this is one of the biggest differences between the two: Bowie’s music feels spontaneous and almost improvised, while Jackson’s music is unbelievably detailed, highly polished and lavishly produced.

Elizabeth: I agree with you both. We can underestimate the sheer complexity of the recording process, and the quality vs. quantity argument is always very relevant. However, the rate of output of one album every four years is a relatively slow output. On the 2001 Special Edition of Bad, there are some lovely interviews with Quincy Jones and he talks about having to make final cuts with Jackson. It seems like an arduous process. In the music industry the longer one is away, the more releases are produced in the interim, the more publicity dissipates, and the more work it is to make the next album a success.

Lisha: That’s a great point, although many artists worry about overexposure as well. It must be like walking a tightrope to get it just right!

As you’ve both mentioned, Michael Jackson’s inaccessibility probably did lead to negative publicity. Sony executive Dan Beck talked about this in a recent interview:

A lot of people in the media were unhappy with Michael because he didn’t talk to them and Frank DiLeo [Jackson’s manager] essentially kept him away from the press, I think with good reason because Michael only had so much to say and he also was a very vulnerable guy. He wasn’t media savvy in the way of sitting down with a journalist and really having that engaging conversation. He was just too much in a bubble.

Frank kept him away, so with all the success that he had there were some media people who were very frustrated that they couldn’t talk to him. So, when things started to crack and there were more odd entities in his life, it started to turn negative.

Karin: But it was also Dileo who – together with Jackson – made up that weird hyperbaric chamber story, which gained Jackson a lot of negativity. And I read somewhere that Jackson liked the mystique of not being too much on TV or in the public eye.

Elizabeth: Do we know this for sure? In Man in the Music Joe Vogel writes:

[H]e cultivated a persona that kept people guessing (and talking). He liked the idea of being mysterious and elusive. He was fascinated with masks, costumes, and metamorphosis. Around this time, he even began to embrace and perpetuate the public perception of his strangeness and eccentricity. (106)

Lisha: I wonder if all of the above is true. If DiLeo planted the hyperbaric chamber story, I think there’s an argument to be made that it backfired. I’m curious if that might be one reason they decided to stay away from the press altogether. But then again, Bowie and others got away with doing and saying many strange and eccentric things, yet didn’t suffer too much for it!

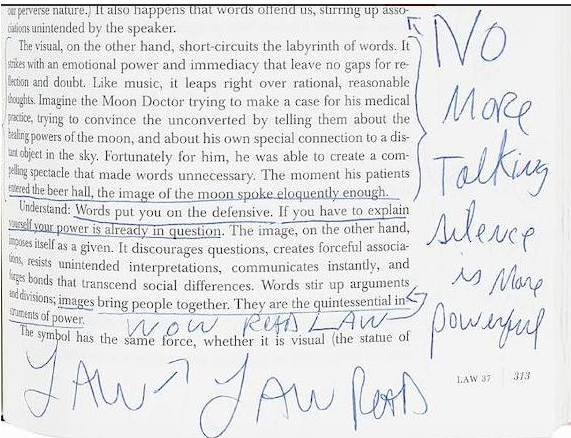

At least for some period of time, it seems Michael Jackson had a deliberate strategy to avoid interviews. I was intrigued by this revealing personal note he wrote in his copy of the book, The 48 Laws of Power by Robert Greene:

“No more talking. Silence is more powerful.”

Here’s a screenshot of Michael Jackson’s handwritten note from Bonham’s website, the auction house that sold his annotated copy of the book:

Elizabeth: Ah, so interesting. It’s this balance between being seen and being a spectacle. The magic is the reveal. To hold back the representation of self until the reveal.

Lisha: I agree! There is so much dramatic tension in this.

Elizabeth: However, “when the media didn’t cooperate with his [Jackson’s] game and turned malicious,” to quote Joe Vogel again, we began to see a very ugly side of Jackson’s representation by the press. The press constructed Wacko Jacko out of the vacuum constructed from this disappearing act. It’s this persona which, coupled with the Monster Persona, seems to be keeping Jackson out of the V & A. Bowie didn’t have the same level of absence in his appearance, so much more about his performance was a performance, whereas Jackson’s “entire life would be performance art,” as Vogel says, “a way to turn the tables on an intrusive media and public that felt they owned him… they were subject to his directions and imagination” (106).

Lisha: I have often wondered why so many journalists felt they were entitled to have access to Michael Jackson. That’s really troubling to me actually, like a display of their power. It obviously spiraled out of control when law enforcement decided to join in the game.

There’s something else I’m curious about, and Karin, I thought you would be well positioned to answer this. The British sociomusicologist Simon Frith, who is one of the key figures in popular music studies, wrote a book in 1987 titled Art Into Pop. Frith argues very persuasively about how the British art education system influenced popular music and its reception. For example, experimental jazz became quite fashionable after it was taken up by art students who deemed it art school chic. It gained social and cultural capital that it previously lacked. So I’ve been thinking about how visual artists function as cultural gatekeepers in popular music, influencing what can be accepted as “cool.”

Do you see this influence in popular music? How much of Bowie’s reception is based on his legibility as art school chic?

Karin: Oh, Lisha, I absolutely think Frith is right. And also what he writes about the blurred boundaries between the so called “High” and “Low” art. These blurring lines were to be found in all kind of art forms. Designers became artists and vice versa, artists played music, created bands, ended up in music, and it is not so strange to see theatrical forms mixed into the performances. In Holland also, lots of art students had bands and one of them, Fay Lofsky, is a trained visual artist who ended up in music, making all kind of experimental sounds, instruments, etc.

I definitely think that a part of Bowie’s reception is based on his legibility as art school chic, which I think is very European. Difficult to describe, but I also believe that the artists who took on popular music, “messed” with it as much as they did with visual art – the “everything is possible” way of thinking. And even though I think Jackson was one of the first and most experimental sound designers of his time, it never came across as such. We know now, but he polished his complex compositions in a way that his music was/is for everyone. Bowie is more niche and therefore may also be considered more avant-garde.

Lisha: That’s a great observation that a niche market often translates into “cool.” I’ve noticed that as well. And I’m also amazed there is so little attention given to how detailed, complex, and experimental Michael Jackson’s recordings are. They are commonly understood as simplistic, which must have to do with perception, since it doesn’t accurately describe the recordings themselves.

Karin: I think, Lisha, that has also to do with the commerce. Michael Jackson was incredibly commercial, or maybe we should say he was a bestselling artist, and somehow people think that those two do not go well together, commerce and art. But there are/were very rich, very well selling great artists, like Basquiat for instance in the beginning of the eighties, and there are equally very good artists that do or did not sell well or not at all. That has nothing to do with whether their art is good or bad. That whole idea is connected with some silly romantic thought that artists should be or are poor. In short, the overall perception is that commercial works cannot be products of high standard art, and that’s how Jackson’s work was treated.

Lisha: You’re so right that there is a very stubborn, rigid cultural idea out there that says commercially successful music cannot be of high artistic value. Yet, as Susan Fast points out in her book on the Dangerous album, certain rock musicians are curiously exempt from this rule! Very suspicious, indeed.

David Bowie gave an interview to National Public Radio’s Terry Gross in 2003, and in it I think it gives us a clue about the relationship of visual art to popular music. Curious to hear your take on it:

Some of us were failed artists, or reluctant artists. The choices were either, for most Brit musicians at that point, painting or making music, and I think we opted for music. One, because it was more exciting, and two, because you can actually earn a living at it.

But I think we brought a lot of our aesthetic sensibilities to it, in terms of we wanted to manufacture a new kind of vocabulary, a new kind of currency. And so, the so-called “gender-bending,” the picking up of maybe aspects of the avant-garde, and aspects, for me personally, things like the Kabuki theater in Japan, and German expressionist movies, and poetry by Baudelaire, and it’s so long ago now — everything from Presley to Edith Piaf went into this mix of this hybridization, this pluralism about what, in fact, rock music was and could become . . .

It was a pudding, you know? It really was a pudding. It was a pudding of new ideas, and we were terribly excited, and I think we took it on our shoulders that we were creating the 21st century in 1971. That was the idea. And we wanted to just blast everything in the past.

Karin: Yeah, and to come back on the difference in culture, this is definitely one of them. Not to downplay American history, but what Bowie says here is very European.

Lisha: I so agree with you!

Karin: It also came right after the “democratisation wave” that kept most parts of Europe very busy at the end of the sixties and the beginning of the seventies. Artists worked conceptually, which meant that they created controversial work or as Bowie mentions, “we wanted to just blast everything in the past.” That brought also the more improvised feel with it as you mentioned before. Jackson was more into creating perfection, to the extent that, even though he composed many songs, just a few were carefully selected for his album. I saw a little footage after Bowie passed away that showed Bowie on the floor of his studio with a pair of scissors cutting up text that obviously became a lyric for one of his songs – so a massive difference in the creative process. He also did not spend as much on a record as Jackson did.

Lisha: I found this short clip of Bowie demonstrating his “cut-ups” technique:

Karin: Brilliant! Lisha, that to me is what I wrote before, about the visual artist messing with (pop) music, and therefore I believe the influence art had in this music. It’s kind of creating a collage but then for lyrics of a song – sort of a Matisse way of creating a new colorful picture, but now creating “colorful” lyrics. Brian Eno (Roxy Music) had the same background and way of creating, and it was definitely an influence in pop music.

Lisha: That’s such a good point. I think we can see how Bowie used these artistic concepts and how it enhanced his image as art school chic.

Karin: It is by the way interesting to read that Bowie did not like performing that much, where Michael always tried to create the biggest show on earth. So Bowie is more for a niche audience than Jackson, and that gives this “avant-garde” feel.

Lisha: Yes, and isn’t it interesting that Bowie managed to retain his avant-garde appeal, even after his act became very big business?

I’ve been thinking a lot about how David Bowie and Michael Jackson were both strong visual artists themselves. To my eye, Bowie’s artwork expresses a more dystopian vision of the future and conforms to an avant-garde chic aesthetic, while Michael Jackson takes a very different approach, more towards a fantasy and utopian impulse. I wonder if we can relate this to their musical ideas as well.

For example, Willa and Joie wrote a wonderful blog on “Will You Be There,” and they described how Michael Jackson quotes Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony in the intro to the song, using it like a hymn to express a utopian vision of brotherhood. It sets up the song by first suggesting a vision of the world as it could be.

As early as 1972, Bowie also used portions of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony as an introduction for his live Ziggy Stardust shows. The recording he used is a synthesizer version by Wendy Carlos, which was featured in Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 film Clockwork Orange. However, Beethoven’s music was used both in the film and in Bowie’s show to express a nightmarish, dystopian vision of the future, quite the opposite from how Michael Jackson used the same work. David Bowie described his Ziggy Stardust concept to William S. Burroughs in Rolling Stone:

The time is five years to go before the end of the earth . . . Ziggy’s adviser tells him to collect news and sing it, ’cause there is no news. So Ziggy does this and there is terrible news . . . It is no hymn to the youth as people thought. It is completely the opposite . . . they take bits of Ziggy . . . they tear him to pieces onstage during the song “Rock and Roll Suicide” . . .

I think this demonstrates how David Bowie and Michael Jackson were both particularly adept at musical hybridization, utilizing elements as disparate as Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony in popular music. But it’s interesting to note how they used the very same technique and the same music to express very different ideas. The connection is quite compelling and reveals their difference at the same time.

Another very interesting connection that comes to mind is that they were both a part of the glamorous Studio 54 scene in New York in the 1970s, although once again, their participation might be viewed in very different ways.

Elizabeth: It’s a strange one, Lisha. You’re right. Raven Woods talks about this in a recent post at All For Love Blog: “It was even reported that they had danced together at Studio 54, when Michael supposedly taught David how to do ‘The Robot’!”

Most of the final section of The Dangerous Philosophies is about how Jackson receives different treatment from other artists and why that is. The first thing we have to recognise is that Jackson was a child star. Immediately, that sets him apart from everyone else.

Lisha: Yes. Not only was Michael Jackson a child star, he was a teen idol and the lead singer of a group that is still described as a “boy band,” to make matters worse. Just this past September, Rolling Stone named “I Want You Back” as the “Greatest Boy Band” song ever. Talk about a back-handed compliment! I can’t find any evidence to suggest the Jackson 5 were produced any differently from all the other spectacular Motown acts, so I really have trouble with defining the Jackson 5 as a “boy band.” It’s also pretty clear that the Jackson 5 appealed to adult audiences, even in the early days, thus the late night club dates Michael Jackson worked while still attending elementary school. I don’t believe the Jackson 5 were ever exclusively a youth act, nor did they exclusively appeal to females.

Elizabeth: Yep. It’s true. But sometimes we underestimate the power of the boy band on the collective social consciousness. I recently caught MTV doing a feature on One Direction, and I didn’t realize they were so successful. I also remember when Take That split, people were crying. The Jackson 5 were the genesis of all this global adoration and mass hysteria, and the hold that has makes it so difficult for someone like Jackson to be able to change physically and artistically right before his public.

Lisha: There is just so much social baggage that goes along with being a teen idol and there is no doubt Michael Jackson suffered as a result. I noticed in that even in the new Spike Lee documentary, there is a lot of anxiety about whether or not Michael Jackson was “adult” enough. For anyone who’s interested, here’s a quick overview of the topic from Dr. Robin James: “If You Hate Justin Bieber, Patriarchy Wins.”

Eliza, would you like to say a little more about the Bowie/Jackson comparison in your upcoming book?

Elizabeth: The chapter in my book which discusses Bowie and Jackson is “Horcruxes: Michael (Split Seven Ways) Jackson.” I also compare Jackson to Johann Sebastian Bach, Stevie Wonder and four other artists. I really tried to find a new way of talking about Jackson because he’s so unique. One of the most challenging things is to come up with a language for how we relate to him as audiences and spectators. Jackson is superlative. One of the ways I try and explore this is through metaphor.

Lisha: Wow, that does sound fascinating. What a counterintuitive group of artists to compare! I am so looking forward to reading your book. By the way, what exactly is a horcrux? It sounds like something spooky from a Harry Potter movie!

Elizabeth: I’m really so excited for you to read it. It’s been a labor of love for two years. A “horcrux” is from a Potter movie. It’s a way to cheat death by putting pieces of a soul into objects. For a fuller explanation (and pretty pictures) see: Pottermore. I like this metaphor for Michael Jackson, especially in terms of looking at him from new perspectives. If you look at Jackson through the prism of another artist it becomes easier to articulate who and what he signifies. I also really like the image of a prism because through it white light is revealed to be many colours. Jackson, for me, is like that. I always find more than I was looking for when I look in different way.

Lisha: That sounds like a perfect metaphor. I’m always amazed by how many lenses it takes to view Michael Jackson’s work. Like I was saying earlier, I didn’t really think about David Bowie as a major Michael Jackson influence until I saw the V & A exhibit in London. Then it seemed like such an obvious connection I couldn’t believe I hadn’t noticed it before.

Elizabeth: That’s what happened to me. Every time I found a new person to compare Jackson to I found more connections. I was really inspired by Willa’s book and how she deconstructed the appearance of Warhol in the Scream short film: another horcrux. Jackson met Warhol on several occasions and Bowie played Warhol in a film. There’s a great powerful connection there.

Lisha: For all we know, the three of them were hanging out together at Studio 54! Willa’s analysis is really inspiring, I agree. We also started to tackle a Warhol/Jackson comparison a little while back. Like everything Michael Jackson, there’s so much more to explore.

I wonder how much is known about any possible interaction between Michael Jackson and David Bowie? In Molly Meldrum’s tribute to Bowie written shortly after his death, he reports that Michael Jackson was “a major David Bowie fan.” I had not heard that before, but I must say I’m not surprised in the least.

Elizabeth: I don’t know that much about Jackson and Bowie’s interactions on a personal level, but artistically, they share a wonderful sense of style, enigmatic persona-creation, showmanship and definitely, the power of androgynous self-representation.

Karin: I don’t know how much interaction there was between the two, but if you know Bowie and his artistic life, you can at least see a lot of similarities. Apart from the way they often provoked the world with their music, both also were very good actors. If you know the film Basquiat by artist Julian Schnabel, Bowie plays Andy Warhol, very well.

So, we know about Warhol and Jackson, they met and have a lot in common, and the same goes for Bowie and Jackson, as Elizabeth writes, the androgynous self-representation, showmanship etc. It is interesting to me that the three somewhere meet, and with somewhere I mean the way all three had the ability to cultivate a persona. Warhol kind of started this, Bowie took it and used it throughout his career and Jackson did the same. All three were exploiting the boundaries between the artist and their art. However, I think the relation between Jackson and Bowie or Warhol is not that clear at first hand for a lot of people.

Elizabeth: But that’s because Jackson has only really started meriting serious academic discussion posthumously. So when we start with something simple like Ziggy Stardust, the stage character Bowie created, with (like Harry Potter) a lightning bolt on his face. He lands on stage, an alien from mars, a spectre. Jackson did the same in the HIStory tour. He landed in a spacecraft in a gold and silver spacesuit.

Lisha: I think this points to one of the most important connections between two: the sheer theatricality of their performances. As popular music scholar John Covach recently noted, there were a number of rock musicians back in the 60s and 70s bringing strong theatrical elements into their work, but Bowie seemed to really take it to another level.

Elizabeth: He completely does. Also, if we think about Glam Rock, it’s all about the show. Making it bigger and more outlandish than ever. I read in David Bowie: Style that he went to learn stagecraft and stage design and then he started to incorporate a lot of what he learned into his productions.

Lisha: I can definitely see how this must have influenced Michael Jackson. Bowie even said that as young musician, he dreamed of writing for musical theatre:

I really wanted to write musicals. That’s what I wanted to do more than anything else. And because I like rock music, I kind of moved into that sphere, somehow thinking that somewhere along the line I’d be able to put the two together. And I suppose I very nearly did with the Ziggy character … My point was I wanted to rewrite how rock music was perceived and I thought that I could do some kind of vehicle involving rock musicals and presenting rock and characters and storyline in a completely different fashion.

Elizabeth: Bowie really understood that a performer is far more than the music. They are a character within their viewers’ minds. The world of the celebrity is often so distant from their experience that they might as well be aliens. Bowie wielded the power of a persona so expertly, Ziggy Stardust became entirely separate from him.

Lisha: Raven Wood’s wonderful post you mentioned really gets into this. Michael Jackson and David Bowie are both incredibly theatrical musicians and performers, but the major difference is that Bowie’s alter egos were perfectly legible as theatrical roles, while Michael Jackson’s were not. As John Covach said, “Michael Jackson was still Michael Jackson.” I think that’s a crucially important distinction.

To prove the point, we don’t need to look any further than Jarvis Cocker’s disruption of “Earth Song” at the 1996 Brit Awards. Cocker told The Guardian’s Lucy Siegle in 2012 that he protested this performance because he objected to Michael Jackson “pretending to be Christ.” Siegle writes:

Does [Cocker] feel remorse for that stage invasion incident at the Brits in 1996 now that he’s engaged with the Arctic and other environmental issues? After all, Michael Jackson was merely giving an epic performance of “Earth Song,” presumably directing our attention to the strife of the planet. “Well, and pretending to be Christ,” says Jarvis, only slightly rolling his eyes. “It is a right good song, obviously.”

The same year Jarvis Cocker gave the above interview to The Guardian, he praised Bowie’s use of alter egos in a BBC special titled David Bowie & the Story of Ziggy Stardust, showing a great deal of reverence for Bowie’s theatrical roles.

While I’m not at all convinced Michael Jackson was “pretending to be Christ” at the Brit Awards, I would be curious to hear Cocker’s take on other actors who have played the role. For example, David Bowie played the role of Pontius Pilate in Martin Scorsese’s 1988 film The Last Temptation of Christ. He did a very powerful scene opposite Willem Dafoe as Christ. Is Cocker similarly offended?

What about Bowie’s 1999 album cover ‘hours. . .’?

According to Nicholas Pegg, David Bowie confirmed the cover photo was inspired by Michelangelo’s La Pieta, a sculpture of the Virgin Mary cradling the dead Christ. I’d love to know Cocker’s thoughts on Bowie as both the Virgin Mary and Christ!

And what about David Bowie “pretending to be Christ” in his 2013 video The Next Day?

I noticed Cocker didn’t seem to object at all in the interviews he gave following the video’s release.

Elizabeth: You’ve hit the nail on the head, Lisha. Bowie was clearly playing different roles but Jackson left us with ambiguity because, being “Michael Jackson” was the role. There’s a vacuum between person and persona. In my essay, “‘Throwing Stones to Hide Your Hands’: The Mortal Persona of Michael Jackson,” I deconstruct these personas. There’s a fissuring of Jackson’s reception which makes it difficult for us to come to the kind of agreement needed to legitimise him in art and culture. Everyone is looking at the same artist and seeing something different.

Lisha: This is an excellent point. There is still no consensus on Michael Jackson and I think there is a segment of society that wants to punish him for his transgressions. Your excellent article compares Michael Jackson’s reception to a biblical stoning. Doesn’t Jarvis Cocker’s protest reflect this punishing attitude as well?

Elizabeth: That is entirely true. Unfortunately, because of the ways in which Jackson bucked the trend and crossed boundaries, he becomes the scapegoat for a lot of society’s neuroses. I recently read a wonderful essay by a student, Maya Curry, called “But Did We Have a Good Time? An Examination of the Media Massacre of Michael Jackson.” It won an award in 2010. There was almost a sense of glee in the way in which Jackson was hounded on every front. Primarily by the press but also by stalkers and admirers. Germaine Greer wrote this in her obituary for him in The Guardian. It brings to mind the Shakespeare quote, “here’s much to do with hate, but more with love” (Romeo and Juliet 1.1.165). The stoning was part and parcel of everyone who made him, the press, the public and even the overwhelming adoration he endured which made it impossible to go anywhere anonymously.

Lisha: Wow, that’s really it! And thank you so much for mentioning Curry’s essay. You’ve given us so much to think about in terms of Michael Jackson’s reception and how David Bowie made parallel moves to a very different effect.

There’s just so much more to say about the connections between Bowie and Jackson, especially how they both created music with such strong visual elements. So in closing, maybe we should let some imagery do the talking. Thank you so much Elizabeth and Karin for joining me and for such a wonderful discussion!

Posted on February 25, 2016, in Michael Jackson and tagged David Bowie, Elizabeth Amisu, Karin Merx, Michael Jackson. Bookmark the permalink. 8 Comments.

Brilliant essay as usual. Never really thought of the paralells of Michael and David before.

Dancing had come through once again with a fascinating post. Thanks so much! Made me think. A lot. A lot to think about. And, I have so many questions, knowing next to nothing about David Bowie.

So, would you say that David Bowie had the broad sex appeal that MJ had? Or was he more of a niche sex symbol?

Did his mysterious sexuality — His claimed to be gay, then bisexual. But it appeared his real life interests were women — his first wife Angie, second wife Iman, Susan Sarandon, Oona Chaplin…–make him more attractive?

Do you see any connections between Labyrinth and Ghosts?

Hi Eleanor,

That’s a really interesting idea: Labyrinth and Ghosts. No I hadn’t thought about it, but would love to hear your take on it! Did you know Michael Jackson was strongly considered for the role of Goblin King as well? http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0091369/trivia?item=tr2220630

Those are all great questions about David Bowie and sexuality and I think it’s a huge topic. In general, I was really struck by how the TV tributes I saw following Bowie’s death went out of their way to construct David Bowie in heteronormative terms: a loving husband in a fairytale marriage with his glamorous wife, a devoted and doting father. In print, I found a number of articles focusing on his omnisexuality, like this one in the NYT: http://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/14/style/was-he-gay-bisexual-or-bowie-yes.html?_r=1

And then there’s this – the unwritten rule that teenage groupies are a perk that comes with being a (great white male) rock-n-roll superstar: https://www.thrillist.com/entertainment/nation/i-lost-my-virginity-to-david-bowie?ref=twitter-869 To say it makes me angry that Elvis et al get a pass on dating 14 yr. olds is an understatement.

Here is some analysis that conflates the false accusations against MJ with Bowie’s appetite for underage girls: http://rebeccahains.com/2016/01/11/reconciling-david-bowies-genius-with-rape/ (excuse me while I go let out a primal scream!)

Another connection between Michael Jackson and David Bowie – Bowie married Iman, but Michael got to kiss her in the short film for Remember the Time!

As to why Bowie was treated as a serious artist, while Michael was not, it’s the 800 pound gorilla in the room – racism. Michael was a black man (hear that, Joseph Fiennes?), while Bowie was a white European male. Black men are often grudgingly considered to be talented by nature, but depth and complexity are reserved for whites. It’s as simple, and sad, as that.

I must say that I’m blown away by the assertion that pop music was “more a British invention than an American”, but not in a good way. I’d like to be more polite, but that’s ridiculous.

Hi VC,

That’s a great point about Iman! I should go back and add some photos to the collage.

I’m with you about racism as the 800 pound gorilla in the room. Everything really does come back to that, doesn’t it? The more I think it through, the more I hit against that brick wall.

I love what you said: “Black men are often grudgingly considered to be talented by nature, but depth and complexity are reserved for whites.” That’s especially interesting when you think about how Bowie’s music feels spontaneous and almost improvised, while Michael Jackson’s recordings are unbelievably detailed and polished, involving huge investments of time and money. Yet, it’s Bowie who has the status as an important artist and musician while Michael Jackson is often perceived as a popstar. Go figure. Even understanding the artistic trends Karin explained so well, I can’t ignore the privilege associated with the “great white male.” It’s incredibly sad, as you say.

I’ll let Karin say more about what she meant by pop as a British invention. But in the meantime, it was my understanding that she was talking about “British Pop,” which is a sub-category of popular music that “Glam Rock” and David Bowie belong to. Here’s a quick Wiki definition if you’re interested: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_pop_music

Speaking of classic clowns, this is from the Los Angeles Renaissance Pleasure Faire, July 9, 1985 (thanks Matilde Beatriz Latini and MJ Photos Collectors): https://scontent.ftul1-1.fna.fbcdn.net/hphotos-xla1/v/t1.0-9/10533431_10208458259798022_1581986501192955441_n.jpg?oh=0bdf670cfaabce056aec745a02a68419&oe=576C4003

Both Bowie and MJ have been my two great musical/performance loves and I’ve often noticed similarities between them as artistes. Great to see a full-blown essay on this.

Amazing discussion. You guys did it all right! It’s really sad to see how the majority still tends to dismiss Michael.